Background

In November 2022, 58% of Angelenos voted to pass the United to House Los Angeles (ULA) ballot measure, commonly referred to as the “mansion tax,” to fund affordable housing. ULA is a Real Estate Transfer Tax (RETT) on high-dollar real estate transactions that would create a permanent and robust revenue source for programs to build affordable housing and address homelessness. Under the new law, any real estate sales between $5 million and $10 million pay 4% tax rate, and 5.5% on any sales over $10 million.

While Real Estate Transfer Taxes are not rare, the ULA measure has several features that make it an important example for other regions and the state: a community-driven collaborative process to design the policy, a progressive tax structure that equitably spreads the burden of paying, support for a comprehensive set of housing programs that have revenue dedicated to community-owned housing, and a robust and transparent process for community governance of the fund.

Policy Design through Community-driven Collaborative Process

Several decisions by ULA campaign organizers resulted in a more collaborative and grassroots process that built greater power and shaped a policy that reflected a broader set of interests and community needs. The ULA campaign itself, and the years of relationship building and coalition work, is well detailed in Los Angeles’ Housing Revolution by Peter Drier. Here, we focus on the role of a voter-initiated ballot measure, policy drafted by community organizers and local policy experts embedded in housing justice work, and a cross-sector campaign coalition as key components of early power-building.

ULA Coalition

United to House LA (ULA) was drafted by an “unprecedented coalition of labor unions, tenants’ rights and community organizing groups, nonprofit housing developers, providers of programs for the homeless, and faith-based groups.”

Figure 1: ULA Steering Committee

Labor unions (building trades) and affordable housing advocates are often at odds over prevailing wage requirements that make costs of development higher, but affordable developers saw the benefit for considerable and consistent funding, and building trades saw the benefit of more jobs for their members. “Part of organized labor’s recent renewal,” Dreier notes, “has been a growing recognition that unions tend to do better in gaining support and winning workplace elections – and do better at election pro-worker political candidates - when they address the social and community concerns of their potential members (such as healthcare, childcare, and housing) as well as their workplace problems.”

Voter Initiated

In California, measures can be put on the ballot by elected officials or by voter initiative. Instead of finding a legislative sponsor, the ULA coalition used their collective wisdom to 1) draft the ballot measure, 2) recruit more groups to participate in the campaign and endorse the measure, and 3) develop a campaign strategy including raising money, crafting a winning message, and mobilizing voters. Ultimately, the coalition gathered more than 98,000 signatures to put the measure on the ballot in summer of 2022 and begin gathering momentum for the election in November.

The ULA coalition spoke to voters’ anxieties on increasing housing insecurity and proposed solutions aimed at both the shortage of affordable housing and root causes of homelessness in Los Angeles. In bringing together connected issues of rising housing costs and increasing job precarity, Measure ULA bridged between groups focused on tenants and groups focused on workers. “Los Angeles is both a city of renters and a city of workers,” writes Dreier, “Most renters are workers, and most workers are renters. This double burden – exploitation by landlords and employers – has deepened in the past decade.”

Drafted by Community Organizers and Policy Experts

The relationships built across housing justice groups and labor union organizers then supported the next phase of drafting ULA policy to serve the diverse needs and continue expanding the coalition. Throughout the campaign, advocates emphasized the ULA solutions and strategies came directly from activists and social service providers, not elected officials. Raymond specifically noted in their December 2021 press release, “LA’s not-for-profit neighborhood organizations and community members have come together, with the assistance of local policy experts – not politicians – to create a ballot initiative that will address homelessness by keeping people in their homes and dramatically increasing the supply of housing that is affordable for Angelinos.”

The ULA tax comes after disappointments with Measure HHH, a $1.2 billion bond for affordable housing passed by Los Angeles voters in 2016. Thus far, developers have leveraged HHH funds with county, state, and federal dollars to create a pipeline of 10,510 permanent supportive and affordable housing units, but left many new models of limited equity housing development ineligible.

Progressive Tax Structure

The approach to the ULA tax relies on a progressive tax structure: targeting rates to those with most capacity to pay. Local Real Estate Transfer Taxes (RETT) around California average around [0.5%] and apply to all real estate transactions, regardless of value. Measure ULA joins San Francisco’s RETT for homelessness funding, the City of Richmond, and Culver City in targeting taxpayers with the most capacity to pay: those selling high value properties.

The ULA ordinance increases the city transfer tax – customarily paid by the property seller – to 4.45% on property sales valued between $5-10 million. Any property sale more than $10 million pays an increased tax of 5.5%. The tax thresholds would rise with inflation over time. Any nonprofit organizations with assets under $1 billion are exempted from the higher rate, but otherwise applies to apartment complexes, office buildings, shopping malls, and other properties selling for more than $5 million.

The measure was nicknamed the 'mansion tax' because it would only affect about 4% of property sales and adjust tax thresholds to rise with inflation to target millionaire and billionaires in perpetuity. (This is particularly important in California and its local jurisdictions where a theoretically progressive tax, the property tax, becomes increasingly regressive.)

Despite fear mongering from real estate political lobbies, the targeted tax structure meant a vast majority of Angelenos would never purchase property expensive enough to trigger the increased fee. Researchers found no evidence that the tax would impact rents for commercial or residential tenants, because rent is determined by markets, not by transaction costs taken on by the seller. Further research from UCLA outlines modifications to ensure the tax does not impact the construction of new, market-rate construction.

Realizing the redistributive potential and implementing the policy priorities will of course rely on realizing revenue from the new tax. ULA revenue estimates, explored in the following section, have fluctuated over the course of the campaign and early stages of implementation. Regardless of the actual money raised, LAHD will see a significant increase from its 2022 operating budget.

Comprehensive Housing Programs

In part as a response to the limitations of Measure HHH, a bond measure for a one-time infusion for developing new affordable housing units, Measure ULA includes a wider variety of housing development models and housing program needs. In addition to gap funding for new construction of traditional multifamily LIHTC projects, the 70% of revenues used for affordable housing programs also includes a set aside for alternative ownership models, a program to fund acquisition and rehabilitation of existing buildings, and capacity building funds. This allows taking advantage of motel and hotel conversions for temporary supportive housing as well as offsite construction tools cutting development costs.

The other 30% of the House LA Fund are designated for a variety of homelessness prevention programs including tenant outreach & education, tenant protections, income support for those on fixed income, and emergency rental assistance. Instead of simply funneling money into existing avenues, the spending priorities reflect the diverse nature of the housing crisis that needs both immediate relief for those under threat of displacement and construction of new units for the long term.

Figure 2: House LA Fund, Program Spending Breakdown

United to House LA, Initiative Measure to be Submitted Directly to the Voters

Community Ownership Set Aside

The evidence of community power is written into the legislation: Measure ULA protects a portion of new revenue for “alternative ownership models” and incorporates new community governance tools to ensure ongoing community participation. This type of accountability can ward off cooptation from status quo actors while allowing for flexibility to adapt to the (inevitably) changing housing landscape.

ULA is unique in allocating portions of this new revenue stream to specific housing programs: explicitly protecting dollars for underfunded and underdeveloped programs and providing a framework for governance over the funds. The coalition was clear in prioritizing housing production and rental subsidy funding for Acutely Low Income Households, Extremely Low Income Households, Very Low Income Households, and Low Income Households.

Under the Affordable Housing Program, 22.5% of total House LA Program Funds will go towards Alternative Models for Permanent Affordable Housing. This bucket of funds will go to projects developed by Community Land Trusts, Limited Equity Housing Cooperative or non-profits in which residents participate directly and meaningfully in decision-making. Where feasible and desirable, these projects will include resident ownership and use public land.

Within the Alternative Models for Permanent Affordable Housing, there is language and requirements that prioritize Collective Ownership models including Limited-Equity Housing Cooperatives, Community Land Trusts, and similar entities:

- Rental Covenants: any resale of rental property funded by this initiative shall be restricted to non-profit entities, Limited-Equity Housing Cooperatives, and Community Land Trusts

- Owner-Occupied Housing Covenants: initial sales and all resales of owner occupied units shall be restructured to Limited-Equity Housing Cooperatives or similar entities providing for resident ownership and affordability in perpetuity

- Qualification: Community Land Trusts and Limited-Equity Housing Cooperatives may qualify for funding without demonstrating a history of affordable housing development/property management by partnering with experienced non-profit organizations or showing evidence of staff capacity.

- Note: the success of partnerships between CLTs and CDCs can be seen in the LA CLT Pilot Program with Los Angeles County

- Capacity Building and Operating Assistance: a portion of funding will go towards

- Supporting single family and cooperative Homeownership Opportunities including but not limited to down-payment assistance, shared equity homeownership, and predevelopment funding

- Capacity building funding for Community Land Trusts and other organizations that serve and have representative leadership from Disadvantaged Communities and facilitate tenant ownership

- Oversight Committee Seat: Seat #5 out of 15 will be an individual with at least five years experience in non-profit Community Land Trusts or community development corporations

Community Governance

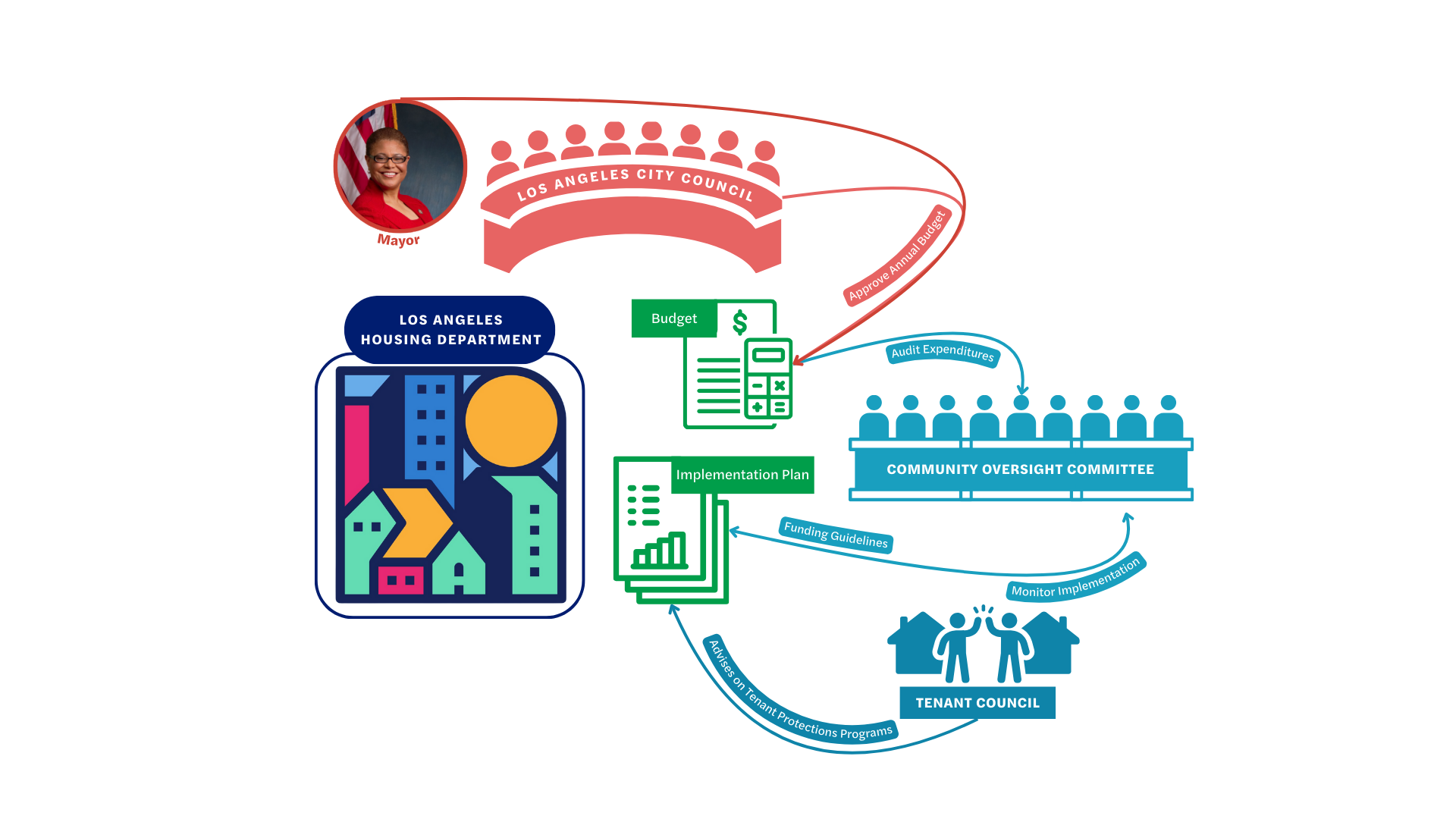

A key aspect of the ULA Measure is provisions for a Citizen Oversight Committee and a Tenant Council. The Citizen Oversight Committee component mandates 13 voting members and 2 advisory members to support youth leadership development. Members are recommended by LAHD staff and appointed by the Mayor. Each seat of the Citizen Oversight Committee is designated to be representative from a specific group: 1) Housing Development, Preservation, and Finance, 2) Renter Protection & Support, 3) Lived Experience & Expertise, and 4) Youth.

While not a decision making entity, the Citizen Oversight Committee will develop funding guidelines, housing-needs assessments, monitor program implementation, and audit fund expenditures. The decision power remains with the Mayor and City Council to propose, amend, and adopt the City budget as long as it follows the allocations set by ULA. The Committee will provide transparency and accountability to the House LA Programs through audits, advising for the Mayor, Department, and City Council, and making recommendations regarding implementation and expenditures. Additional responsibilities for the Oversight Committee include holding public hearings, investigating potential conflicts of interest, holding an annual town hall to report on progress and shortcomings to the public, and making any adjustments to the Program Guidelines.

There will also be an appointed Tenant Council that monitors and advises the LAHD on implementation of tenant protections and develops strategies to address Fair Housing Act violations and violations of tenant rights. The Tenant Council will receive updates on rent relief programs, landlord opt-outs from rental assistance programs, and tenant harassment and eviction data, and may make recommendations that reduce evictions, displacement, and increase tenant access to legal services. The Tenant Council will be appointed by City Council and will be composed of tenants or currently homeless individuals living in the City. The City Council will ensure that there is diverse representation on the Tenant Council with respect to income level, housing status, race, gender identity, sexual orientation, national origin, immigration status, source of income, religion, age, disability, familial status, and primary language.

Figure 3: Measure ULA Governance Model

United to House LA, Initiative Measure to be Submitted Directly to the Voters

Looking Ahead: Implementing Housing Justice, Fighting Legal Challenges

The strength of campaign organizing and collaborative policy design has been essential to sustaining momentum as Measure ULA faces the usual opposition from entrenched real estate power throughout implementation. Measure ULA is facing stalls from a withholding real estate industry and legal challenges from well-funded anti-tax groups. Despite the expected opposition, the COC continues to meet quarterly, and is contemplating additional exemptions to the RETT to counterbalance any economic distortion.

Revenue Delays

Early estimates anticipated between $600 million and $1 billion annually in new revenue from the ULA tax structure. In its first implementation report published in March 2023, LAHD estimated approximately $672 million in ULA funding for the year. As growing interest rates stifle home purchases and the real estate industry “innovates” workarounds, early ULA revenues have fallen below the original estimates. After 4 months the city reported collecting $55 million in ULA revenues, by November 2023 LA had collected $143 million. Because of risks due to pending litigation (described in the following section) Mayor Bass only included $150 million ULA funds in their FY 23-24 budget proposal.

Figure 4: ULA Implementation Timeline

Click here to open and enlarge PDF in another window

Legal Challenge

The current legal challenges are built on the decades of anti-tax lobbying and the more recent $8 million spent by California’s largest landlords, developers and property managers on a ULA opposition campaign. While LA’s wealthiest property owners and their real estate agents schemed on how to circumvent the new law, a direct lawsuit and a constitutional amendment have emerged as post-election strategies to repeal ULA.

The Howard Jarvis TaxPayers Association (HJTA) and Apartment Association of Greater Los Angeles (AAGLA) moved swiftly after the November election to file their case against the City of Los Angeles on December 22, 2022. Their case claims the new tax is illegal because it is assigned for a special purpose (housing) and not in the city’s general fund. In previous cases on new local revenue for specific programs, the California Supreme Court has honored voter-initiated ballot measures passed with a simple majority. The case has been dismissed by both federal and local courts.

The Taxpayer Protection and Government Accountability Act is a larger attempt to make taxes, like Measure ULA, harder to pass and require any new special tax pass by 2/3s in local government and 2/3s vote of the local electorate. The proposal, led by Kilroy Realty and the California Business Roundtable (and supported by California NAIOP and JFTA), would apply retroactively to any new special tax measures passed in the last couple years to specifically invalidate Measure ULA. The campaign got more than one million registered voters required to place the proposal on the 2024 ballot, but in September 2023 Governor Newsom filed a petition to have the initiative removed from the ballot because it is already destabilizing government finance and poses an immediate threat to vital state and local services. The campaign has received more than $17.3 million in contributions, and more than $7.9 million from California Business Roundtable Issues PAC by the end of December 2023.

Conclusion

With a massive funding gap being the main barrier to addressing the housing crises in California, the ULA measure offers hope that grassroots collaboration can design and win substantial new funding. The attention to the diverse housing solutions needed – from emergency rental assistance to community land trust acquisitions to support for tenant protections and more – shows how collaboration that builds bridges across sectors generates more comprehensive and effective policy. The intense resistance by property owners and realtors is evident in their willingness to stall transactions, dedicate television programs to getting their message out, and attempt to pass state ballot propositions that would devastate future possibilities for increasing revenue to meet California’s housing needs. ULA provides an illuminating lesson in what’s possible when bold initiatives move forward.