Ann Arbor Water Tower. Photo by Dwight Burdette

Executive Summary

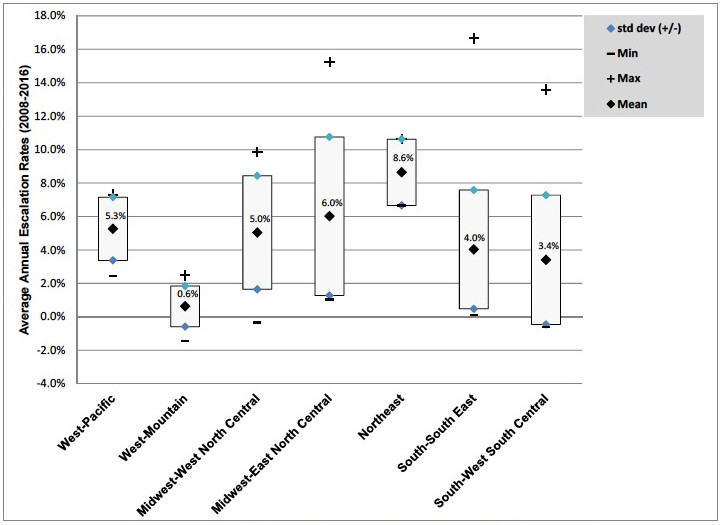

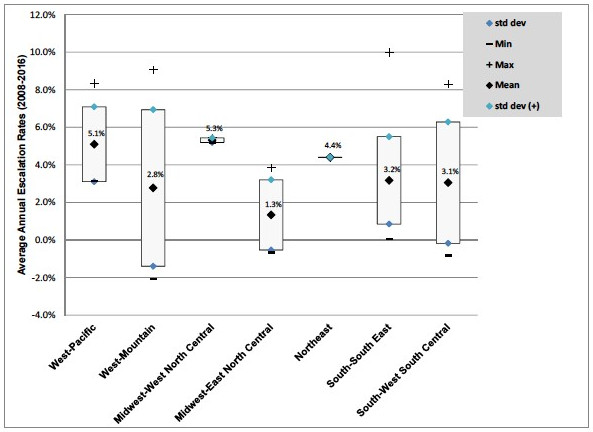

The Context of Water Affordability

In the last few years, increased attention has been paid to rising costs for water and wastewater services, including the need to upgrade and replace water and wastewater infrastructure across the country. In a survey of 260 water utilities and 180 wastewater utilities across 42 states, average water rates increased by 40 percent and average wastewater rates increased by 24 percent between 2008 and 2016 alone. Regional price escalation was highest in the Midwest and Northeast, although these regions had the lowest average water rates overall, while West-Pacific states had the highest prices overall, but a modest price escalation rate.Regarding the results of the study’s regional price and price escalation levels, the report notes: “Some regional trends are observed; however, it is important to note that regional sampling is variable and limited. For example, the Northeast region is represented by only two utilities. Based on the utilities observed, it would appear that the Midwest and Northeast have some of the lowest average water rates (see Figure 8) 5; however, Figure 7 would suggest that these same regions have had some of the highest annual price escalation rates in recent years. Conversely, although the West-Pacific states have the highest average regional water rates (see Figure 8), the annual price escalation rate, at 5.3% (see Figure 7), is only slightly higher than the entire sample average of 4.1%. There are a wide range and variability in both water volume rates and historical price escalation rates across the southern utilities observed in this study, with an average escalation of about 3.5% across the entire southern region. The study’s scope did not include an investigation into why such a large variation exists, but these variations are often driven by local infrastructure investments by the given utility (Walton 2017).” They cite the following report that provides information on the influence of price by local infrastructure investments. Brett Walton, “Price of Water 2017: Four Percent Increase in 30 Large US Cities,” Circle of Blue, May 18, 2017, https://www.circleofblue.org/2017/water-management/pricing/price-water-2....1

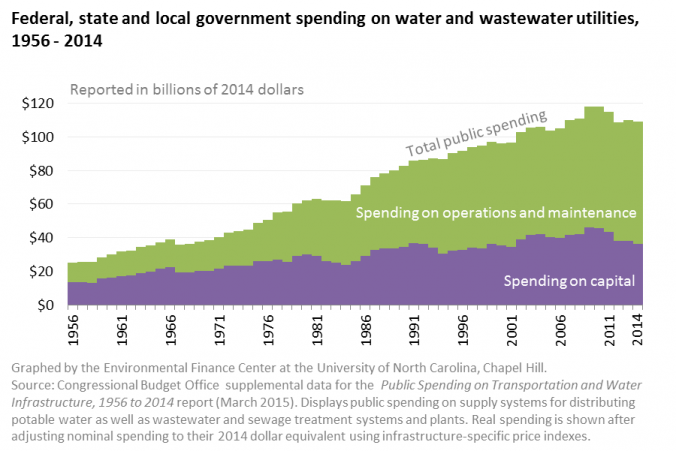

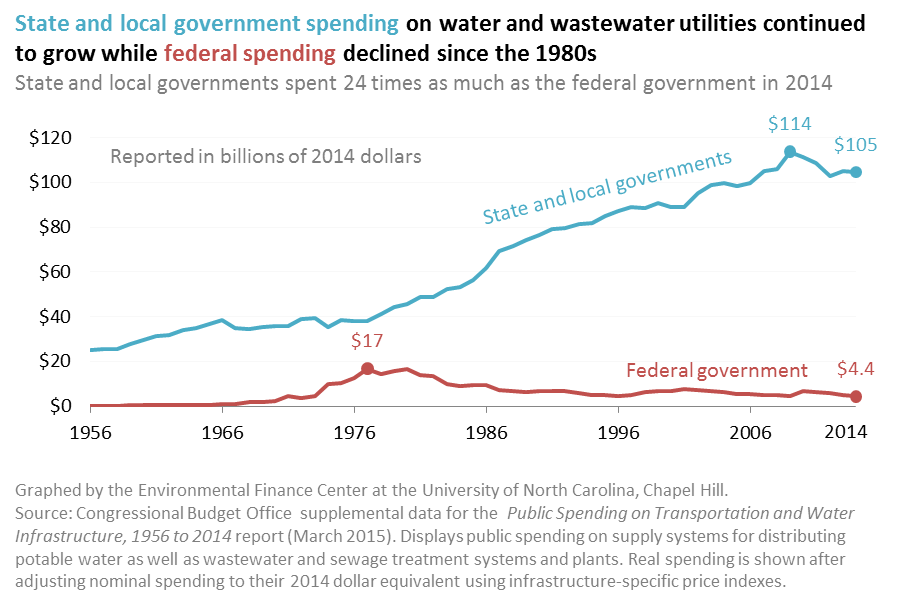

Affordability considerations are especially concerning in the context of declining public investment. While public spending on water and wastewater has increased steadily over the last 50 years, the annual rate of increase has decreased for capital infrastructure, as well as operations and management.2 In addition, of the total public spending on water and wastewater systems capital programs—comprised of federal, state, and local governments—state and local governments account for almost 100 percent.3

Figure 1: Federal, State, and Local Government Spending on Water and Wastewater Utilities 1956-2014

Image source: http://efc.web.unc.edu/2015/09/09/four-trends-government-spending-water/

Figure 2: Source of Expenditures on Local Water and Sewer'

Image source: https://www.usmayors.org/2018/01/10/local-government-investment-in-water...

Figure 3: State and Local Government Spending Decline Since 1980’s

Image source: http://efc.web.unc.edu/2015/09/09/four-trends-government-spending-water/...

Figure 4: "Average Annual Water Price Escalation Rates by Region (2008-2016)"

Image source: https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2017/10/f38/water_wastewater_esc...

Figure 5: "Average Annual Wastewater Price Escalation Rates by Region (2008-2016)"

Image source: https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2017/10/f38/water_wastewater_escalation_rate_study.pdf

These national trends can be seen in Detroit, where the city and the Detroit Water and Sewer District (DWSD) experienced dramatic population decline and disintegration of the local economic base, both before and after the 2008 financial crisis. DWSD-R (DWSD Retail) and the Great Lakes Water Authority (GLWA) continue to need upgrades so they may fulfill environmental quality and public health standards. The system faces significant financial demands to upgrade, maintain, and operate the regional water and wastewater infrastructure. As is the case with most public water and wastewater utilities, local government provides the vast majority of revenue for these purposes. While the larger Detroit metropolitan area serviced by DWSD has experienced modest population growth between 1950 and 2010, the region’s urban core—the city of Detroit—lost 61 percent of its population in that same period. A declining population of users within the city’s center, coupled with DWSD’s institutional structure that places different cost burdens on wholesale suburban customers, makes it extremely difficult to spread overall costs among system-wide users.

Through the bankruptcy proceedings, the Great Lakes Water Authority was created as a state chartered public corporation. Upon the effective date of the lease and services agreements DWSD-R is the way DWSD is described. Former wholesale customers of the DWSD system are now wholesale customers of GLWA, and DWSD-R is also a wholesale customer of GLWA. While DWSD-R retains ownership of the entire system, it is operated and managed by GLWA. DWSD-R maintains specific portions of the system within the city’s boundaries.4

The human right to water depends on the financial capacity to provide access to water. In practice, the demands put upon local government due to the lack of federal investment of infrastructure means that in order for public systems to have the revenue to maintain, operate, and upgrade the system, there must be clear guidance on how to determine who is able to pay and who is not able to pay. This determination is exceptionally important in the growing number of cases in which financially stressed public utilities attempt to maximize revenue through collections enforcement. If a user of the utility is unable to pay, this strategy is ineffective, wasteful of utility time and resources, and a violation of human rights.5

Ultimately, the crux of this multifaceted problem is the need to define affordability in such a way that utilities are able to effectively plan and fund necessary capital improvements, as well as ongoing operations and maintenance, without placing an undue burden on vulnerable populations, especially those who are unable to pay.

Current measures of affordability from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) are widely used but inherently flawed, and have been critiqued by experts, practitioners, academics, government organizations, and even the EPA's own science advisory board.6 Current EPA metrics for water and wastewater use aggregate measures of median household income (MHI), rather than utilizing a place-based analysis. This masks unaffordability in sub-populations within a utility, such as different communities, customer classes, neighborhoods, and demographic groups. Additionally, the use of median shifts the focus away from the low-income segment of the population which is in fact facing affordability issues and is most subjected to behavioral changes in water consumption that impacts utility financial planning.

The findings identified by applying a particular measure of affordability are important for several reasons. If unaffordability is found, permittees are able to negotiate with the EPA to delay or reduce clean water regulations (subject to minimum health standards), avoiding significant legal costs from EPA lawsuits or immediate debt required to finance technological improvements to achieve regulatory compliance.7 Additionally, findings of unaffordability allow beneficial financial terms from EPA-financed state revolving funds that finance infrastructure projects, allowing loans to be converted to grants or even zero-to-negative interest rates.8 Lastly, findings of unaffordability are used as inputs in policymaking wholly separate from the EPA, such as state or local funding decisions around social programs, utility customer assistance programs, and academic, industry, or government studies on socioeconomic characteristics of the populations served.9

This study takes recommendations from experts and government review bodies to develop an alternative metric that uses place-based measures of income. The study first applies the current EPA measures of affordability and then compares the results to two alternative metrics. The first alternative metric is a conservative estimation, introducing place-based data. The second alternative metric is a more realistic estimate that includes place-based data and a focus on households more sensitive to unaffordability pressures. The comparisons demonstrate the extent to which current EPA metrics misrepresent unaffordability, and provide empirical evidence of the true extent of unaffordability. The distributional impacts of current rate designs are also analyzed. The findings are then used to inform discussion of policy alternatives to address utility revenue requirements (including current customer assistance programs), cost allocation, and capital improvements.

Findings

In this study, the EPA and alternative metrics are applied to the DWSD-R service area. The question of water and sewer affordability is one of national significance, and this report adds to the literature by demonstrating the importance of the specific measures used, applicable in both Michigan and other areas across the country.

The first type of metrics studied—the current EPA metrics—find no affordability issues within communities or neighborhoods in the GLWA or DWSD-R service areas, either in the total bill or the separate water/wastewater components.

The second type of metric—what we describe as the conservative specification of an alternative metric—uses local MHI, rather than aggregate measures of MHI. This conservative alternative metric uses census tract MHI to calculate the affordability threshold, introducing data to enable a place-based analysis.

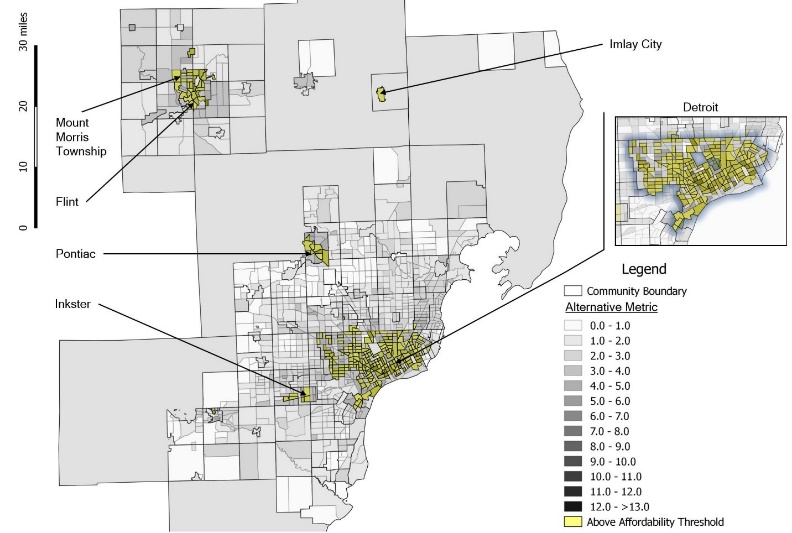

Figure 6: Unaffordable areas for drinking and wastewater costs when using census tract MHI as an affordability threshold

In the image above, this metric finds unaffordability (in yellow) in seven communities, spatially clustered around urban centers, all of which have local MHI below $31,300. Customers within tracts above the metric’s affordability threshold and with incomes under $29,999 comprise 72,185 households in Detroit and 35,864 households within the rest of GLWA.

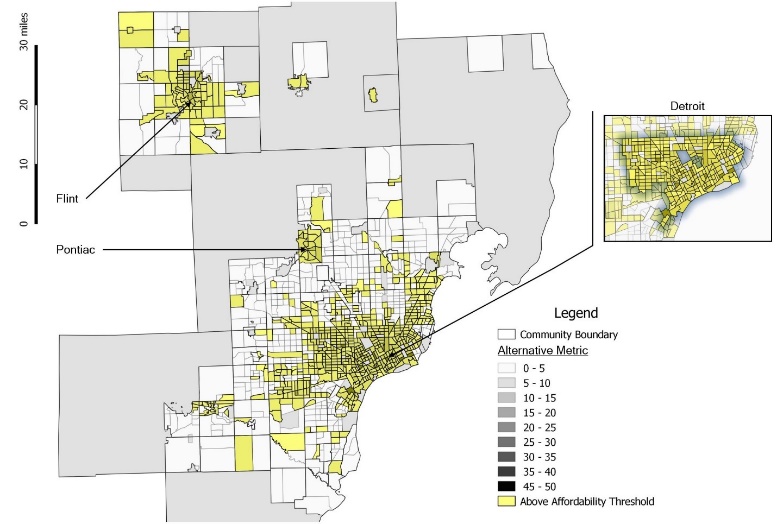

The third type of metric—what we describe as the realistic specification of an alternative metric—uses local income data like the conservative alternative metric. What sets this metric apart is that it changes the focus of the analysis to the twentieth income percentile (the value below which 20 percent of households exist) rather than the median. The twentieth percentile is commonly used as the lower bound of the middle class. Use of this income level for a water and sewer utility affordability metric has been advocated for by scholars, experts, and a prominent government review panel.

Figure 7: Unaffordable areas for drinking and wastewater costs when using twentieth income percentile as an affordability threshold

Applying this metric to the GLWA and DWSD-R service areas in the image above shows unaffordability (in yellow) in 45 communities, all of which have twentieth percentile income below $31,000 (aside from a single outlier facing above-average annual water costs). Unaffordability is again spatially clustered around urban areas, but with this metric, we also see it is more widespread into suburban areas. This spatial clustering pattern is consistent with other studies that have shown “pockets of poverty” using different metrics, which are patches of unaffordability within communities—individual census tracts that rise above the metric threshold within a community that does not itself as a whole break the threshold. Customers within tracts above the metric’s affordability threshold and with incomes under $29,999 under this specification comprise 104,181 households in Detroit and 204,308 households within the rest of GLWA.

In sum, 308,489 households in the GLWA and DWSD-R service areas with incomes below $29,999 are facing water and sewer insecurity. This is meaningful for efforts to create equity and more evenly distribute resources within regional areas through targeted policy measures. Literature has shown that census tracts with median incomes below $32,000 have higher percentages of disabled people, higher unemployment rates, higher levels of public assistance income, higher incidence of sole female heads of household, larger percentages of minority residents, and lower rates of health insurance.

Further, analysis of the data from the GLWA and DWSD-R service areas looking at distributional impacts match these trends, with very clear correlations between the percentage of the population that is African American and census tracts facing the most intense unaffordability issues when using the conservative specification. Using both the realistic and the conservative alternative metrics, the percentage of the population receiving public assistance and percentage of the population with a disability also follow the general patterns of census tracts that rise above the metric threshold, meaning that these vulnerable populations are the customer segments most likely to face affordability issues.

Policy Alternatives

Targeted policy alternatives for addressing unaffordability in Michigan should consider what has been described as a restrictive legal environment. A Michigan Constitutional Amendment and a State Supreme Court case interpreting it (referred to as Headlee/Bolt) found that some utility charges that the utility categorized as user fees were illegal taxes.10 However, there is disagreement among experts and practitioners about how this decision could apply in the context of water affordability policies and institutional practices throughout the state.11 More restrictive interpretations of the Headlee/Bolt case are not settled law as demonstrated by a number of cases brought against townships in circuit court, which have had mixed results.12

Throughout the US, policy alternatives that attempt to address unaffordability fall under two general categories:

- Customer assistance programs: typically short-term policies like temporary assistance, water efficiency upgrades, or flexible billing terms

- Alternative rate designs: long-term policies that structure rates according to certain criteria, like income, usage, or minimum amount of water needed for human health

Both categories of programs are sometimes described as water affordability programs, which can create ambiguity between different parties since both categories offer financial relief in different ways. Notably, the second category can promise a more sustainable resolution to affordability problems.

The design of the customer assistance program offered by GLWA and DWSD falls into the first category. Called the Water Residential Assistance Program (WRAP), it provides bill credits, arrearage (past due bills) assistance, water efficiency audits, and minor plumbing repairs to households with income at or below 150 percent of the federal poverty level and that meet a number of other criteria. The program helps households facing temporary unaffordability crises, but certain features like a two-year cap on participation, minimum payment qualifications, focus on arrearages over bill credits, and limited funding means that it does not offer sustainable relief or address structural causes of unaffordability. In Detroit, the area with the most acute needs and largest WRAP funding, the program is estimated to have reached only 11 percent of qualifying households. Estimated WRAP funding needed to reach the rest of the need in Detroit alone ranges from $32 million to $46 million. It is clear that, even with an infusion of additional funds, WRAP or similar customer assistance programs alone are not sufficient to durably and sufficiently solve the region’s affordability problems.

Customer assistance programs treat the symptoms of unaffordability, but alternative rate designs treat the structural root causes. This study provides the necessary empirical evidence to tailor an alternative rate design and provides a set of recommendations to implement it. The study holds significance for institutions that regulate and operate the 52,000 water plants and 16,000 wastewater treatment plants that serve 86 percent of US residents. Relieving the burdens of affordability problems is urgent, and developing a shared understanding of the degree of the problem will enable better communication about strategies and solutions to address it.

Introduction

Residential water bills have risen consistently since 2010—and annual increases have varied between 8 or 9 percent to 3.1 percent.13 Between 2010 and 2015, there was an overall 41 percent rise in both water and sewer utility service costs.14 Local efforts by stakeholders and policymakers to address affordability have expressed a need for empirical evidence on the extent of unaffordability, what groups those impacts fall on, and how trends have changed over time.15

Water is essential to human well-being. Water is the foundation of health and is used for cooking, bathing, cleaning, and waste disposal. Lack of access to water prevents individuals from full participation in the economy, limiting both their own and their communities’ productivity.16 Special rapporteurs from the United Nations have recently turned attention to the access to clean water and adequate sewer systems as part of the institution’s work on human rights statutes on poverty, water, and sanitation.17 The Detroit Water and Sewer District’s (DWSD) 2014 water shutoffs garnered so much national and international attention that it compelled two UN special rapporteurs to visit the city to speak with stakeholders and impacted communities about the issue.18 The special rapporteurs found that:

Without water, people cannot live a life with dignity… It exacerbates inequalities, stigmatizes people and renders the most vulnerable even more helpless. Lack of access to water and hygiene is also a real threat to public health… In line with the mandates entrusted to us by the Human Rights Council, we would like to underline that the United States is bound by international human rights law and principles, including the right to life as well as the right to non-discrimination with respect to housing, water and sanitation and the highest attainable standard of health. These obligations apply to all levels of Government – federal, state and municipal… When people are genuinely unable to pay the bill, it is the State’s obligation to provide urgent measures, including financial assistance, especially low tariff or subsidies, to ensure access to essential water and sanitation for all. Not doing so amounts to a human rights violation.

At the same time, the special rapporteur explicitly states, “Water and sanitation does [sic] not have to be free.”19 They recognize that addressing affordability is a balancing act between ensuring the human right to water and long-term utility viability.

Between 2014 and 2016, DWSD shut off water to 83,752 homes due to nonpayment,20 and in March 2018 threatened to shut off water to 17,461 more homes after a moratorium on shutoffs ended in early May.21 Utility operators have commented on how they struggle to determine who is able to pay and who is not.22 The spread of residential water shutoffs as a collection strategy erroneously assumes that households can afford to pay. The majority of water shutoffs, particularly residential water shutoffs, are due to arrears accumulated by households’ inability to pay, not a lack of willingness to pay or a desire to "freeload."23

Water and sewer utilities in the US are considered natural monopolies and rate setting is typically dominated by studies that measure the willingness of users to pay (WTP) for water. However, as wealth, wage, and income inequality accelerate across the US, rates for water and sewer utilities set according to WTP is entirely mismatched to the empirical reality that shows some people are simply unable to pay.24 These studies have also shown that lower-income households are most sensitive to increasing water rates—meaning that if there are any changes in the rates, these are the households most likely to use less.25 In the context of extreme austerity and lack of federal funding, the dominant cost recovery rate-setting model neglects the profound role of water and sewer utilities in public health and other cascading effects inaccessibility can create.26

Experts have pointed out that there is a “business case” to be made that addressing affordability offers utilities financial benefits, not just costs.27 In the fiscal year 2016, Detroit budgeted $1.6 million for costs related to customers' inability to pay, such as account collections activities, service disconnections, and payment plan administration. An additional $7.8 million contract has been signed with a water shutoff contractor for future shutoff expenses between 2018 and 2021.28 Such activities could be effective if payments were simply late, but when households are “genuinely unable to pay the bill” as the UN special rapporteurs point out, those collections activities by the utility are essentially wasted resources and effort, going after money that customers simply do not have. Additionally, analysis by Detroit’s water utility found that decreasing the proportion of income that a water/wastewater bill comprises from 8 percent to 4 percent improves collectability by 25 percent and reduces the probability of shutoff by 10 percentage points.29

For many households, and for the local governments that finance system costs, there are already large problems. Local governments and residents of the GLWA service area are among the people and places facing this problem. However, it is not just Detroit facing unaffordability issues: the infamous Flint lead crisis began when the city decided to change the source of its water in an attempt to lower costs,30 and some smaller cities and townships have faced citizen pushback and even lawsuits over rate issues.31 A recent US Government Accountability Office report analyzing water infrastructure found that Michigan has the largest number of large and midsize cities facing declining populations. Of the 14 large and midsize cities identified, all but four are located in southeastern Michigan. Declining populations further complicate the ability of utilities to spread the costs of the necessary infrastructure investments and are generally more economically distressed than growing populations.32

There are economic as well as humanitarian reasons to provide protections related to affordability. This report will use empirical evidence and novel methods recommended by experts and government review panels to determine the extent of unaffordability, who is impacted, and how utilities can make adjustments to address structural affordability.

Background

This section will detail the information needed to understand how utilities set rates and plan infrastructure investments, as well as how existing measures of affordability are designed and implemented. It will end with expert, practitioner, academic, and government critiques of those existing measures of affordability, leading into the Analysis section that proposes and implements an alternative metric, which will be used to inform policy alternatives to address affordability.

Utility Approaches to Infrastructure Investments and Rate Setting

GLWA needs to make $2.8 billion33 in capital improvements over the next five years without placing an extreme burden on the population it serves. Modern utilities use a cost-based approach—allocating costs to different groups (“classes” or types of customers, geographically diverse communities, etc.) based on the cost of including them in a utility’s service—in determining what rates to charge different types of customers.34 According to one of the foundational textbooks for cost allocation and rate design, determining how to do so is difficult and open to interpretation:

Cost allocation is inexact; no single correct approach or method exists. Much depends on the criteria used by analysts… The choice of a cost allocation approach depends largely on utility management objectives and regulatory policy considerations… As in selecting a cost allocation method, the choice of rate design involves tradeoffs among the goals of efficiency, equity, revenue adequacy, and administrative feasibility.35

The American Water Works M1 manual identifies some of those possible utility management objectives as:36

- Full cost recovery

- Revenue stability and predictability

- Stability and predictability of rates

- Promotion of efficient resource use

- Fairness in apportionment of total costs of service among different ratepayers / avoidance of undue discrimination within rates

- Dynamic efficiency in responding to changing supply and demand patterns

- Simple to understand and administer

The manual further identifies distinct situations and pricing considerations utilities must face, such as:37

- Standby rates

- Drought surcharges/rates

- Low-income affordability rates

- Economic development rates

- Indexed rates

As will be demonstrated in this report, there is a lack of affordability in the GLWA and DWSD-R service areas existing even before needed investment costs are added, and clear differences in ability to pay between customer classes. There is also a business case to better incorporate this structural mismatch in utility rate design and cost recovery, enabling savings on collections activity. As the National Academy of Public Administration summarizes:

Ultimately, the challenge is one of maintaining affordability while also recovering the full costs of providing water services, which, in absence of low-income assistance, is limited by low-income households' ability to pay. Rate structures themselves may place a disproportionate share of the burden on low-income households.38

EPA Measures of Affordability

When discussing affordability, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is central to the conversation. This is in part due to the enormous cost burdens on water systems stemming from the federal requirements promulgated in the 1972 Clean Water Act (CWA), 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), and subsequent amendments to those acts. The EPA creates and enforces regulatory standards for this legislation, including compliance with the regulatory status of contaminants in drinking water, source water protection, overflow discharges from treatment plants, and more. In the context of these regulations and associated permitting standards, affordability has a twofold definition: 1) the ability of utilities and local governments to afford capital investments and operation costs required to meet EPA regulations, and 2) the ability of residents within a utility’s jurisdiction to afford the retail cost of water and wastewater service—costs that underpin system revenue.39

Local regulators and utility operators use EPA guidelines in decision-making to promote public health and environmental quality. The regulatory authority of the US EPA and state EPA agencies and their ability to take enforcement action incentivizes systems to work with the EPA to create compliance schedules and take advantage of funding programs offered. Unfortunately, the costs of maintenance and system upgrades needed to meet regulatory standards are often too great for local systems to bear alone. This leaves local governments responsible for covering the large majority of costs and makes user revenue a vital component of the overall revenue needed to cover expenses.

Affordability for households is a primary concern for local governments tasked with setting rates to recover system costs. The EPA’s metrics have become the de facto definition of affordability in the majority of academic and practitioner discourse, including in applications beyond what the EPA originally intended. This has led to widespread critiques of the EPA’s measures, both in theory and practice, which are detailed below.

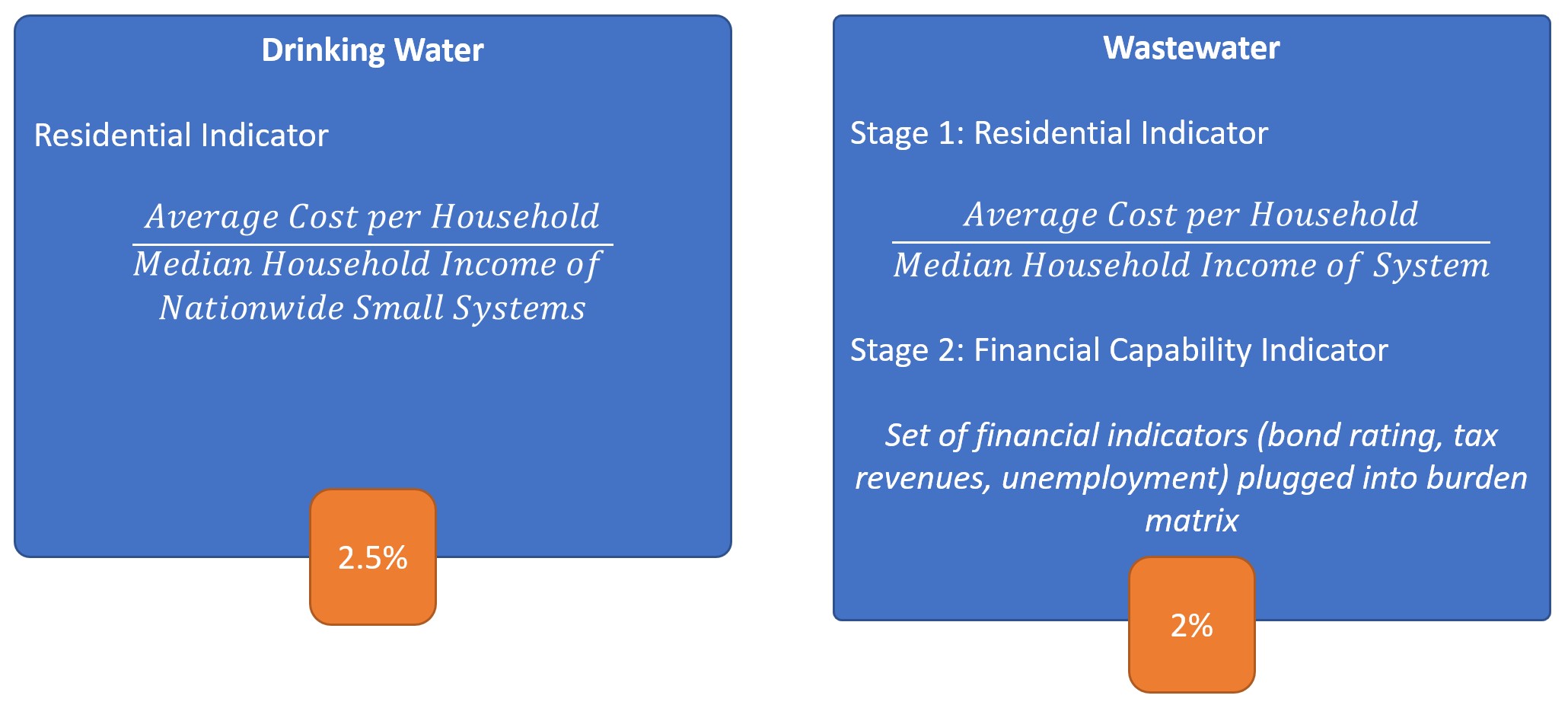

EPA Affordability Metrics

The EPA’s 1997 “Combined Sewer Overflows—Guidance for Financial Capability Assessment and Schedule Development”40 (1997 guidance) establishes a two-phase approach to assess a permittee’s (utility or municipality) capability to meet federal mandates and provide affordable wastewater service. The first stage is a “residential indicator” (RI), which is a ratio of a utility’s average cost per household for wastewater treatment to median household income (MHI) across the system. For large or complex systems that span multiple communities, MHI is a weighted average of MHI for each community, scaled by the size of that community. The EPA stated that an RI threshold of 2 percent system-wide would be deemed unaffordable.

If the 2 percent RI threshold is crossed, a second stage is triggered that implements a “financial capability indicator” (FCI), which uses six economic indicators (bond rating, overall net debt as a percentage of full market property value, unemployment rate, MHI, property tax revenues as a percent of full market property value, and property tax collection rate) combined in a matrix with the RI to reach a finding of “low,” “medium,” or “high” burden.

Taken together, the RI is meant to indicate the ability of a utility’s residents across the system to afford the allocated costs of wastewater service, and the FCI is meant to assess a utility’s ability to fund or finance capital investments required to meet EPA regulations.

For drinking water (drinking water RI), EPA considers a single stage analysis of the ratio of average cost per household to MHI of small systems.41 The MHI for small systems was determined internally by the EPA from data contained in the Community Water System Survey and US Census.42 In practice, this functions similarly to the wastewater RI, but with a national average MHI rather than local. A threshold of 2.5 percent for drinking water is deemed unaffordable.

Figure 8: EPA Affordability Metrics and Thresholds

In either case, if the EPA’s metrics find problems of unaffordability in wastewater or drinking water for a system, permittees can negotiate with the EPA for a temporary “variance” or “exemption” from CWA or SDWA regulations.43 These variances and exemptions differ based on whether the negotiations are over wastewater or drinking water, as well as on the size of the system. The temporary status of variances and exemptions are intended to allow a utility time and financial space to raise the necessary capital for implementing the technology required to come into compliance. During this time, the utilities must implement minimally required technology improvements, hold public hearings regarding the planned variance/exemption, reevaluate water quality results at set intervals, and set a schedule for full compliance. Variances and exemptions are important tools that save utilities significant amounts of money by avoiding legal costs from EPA lawsuits over noncompliance or costs incurred from having to procure emergency bond deals at unfavorable terms.

Another important impact of findings of affordability relates to additional funding sources for utilities. The EPA offers low-cost infrastructure loans as part of the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) and Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF).44 Both are federal-state partnership programs funded by Congress and administered by the EPA, which provide grants to states who then manage individual loan disbursements for capital improvement projects to public utilities. Importantly, the EPA grants states the ability to set project priorities and customize loan terms to meet the needs of “disadvantaged communities” through additional subsidies beyond zero-interest loans, including grants, principal forgiveness, and negative interest rate loans.45 If a utility is not found to have affordability problems, these important financial tools may not be applied.

Lastly, findings of unaffordability by the EPA metrics matter because they can be used as inputs in decision-making wholly separate from EPA regulations, such as state funding decisions for social programs related to utilities, utility decisions on customer assistance programs or alternative rates, and academic, industry, or government studies on the socioeconomic characteristics of customer classes.46

The drinking water and wastewater affordability thresholds are often combined by practitioners, experts, and academics to recognize a total water cost of 4.5 percent as unaffordable.47 The RI, FCI, and drinking water RI will hereafter be referred to as “EPA metrics” collectively or “wastewater metric” and “drinking water metric” individually.

Critiques of EPA Metrics

The EPA metrics have been roundly criticized from a wide variety of sources, including academics,48 industry experts,49 practitioners,50 federal agencies,51 and the EPA’s own science advisory board,52 spanning decades. Until very recently, however, very little action has been taken to address deep flaws in these metrics and their use.

In 2016, the Senate Appropriations Committee directed the EPA to contract with the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) to “conduct an independent study to create a definition of, and framework for, community affordability of clean water”53 that encompassed both drinking water and wastewater. NAPA produced a comprehensive literature review, over 100 stakeholder interviews (including with PA Financial Advisory Board, Council of Mayors, water industry groups, academics, consultants, governmental entities, and others), a stakeholder survey, and a roundtable discussion with stakeholders and experts.54 Their 2017 report produced a set of findings and recommendations related to affordability concerns and improvements to EPA metrics, among other things.

Although both RI and FCI were criticized in literature and by stakeholders as “inaccurate” and “inadequate,” NAPA found that the RI was the “most severely criticized” of the two.55 Stakeholders and the relevant literature agree that:56

- MHI is an inadequate metric for identifying affordability issues for the most vulnerable low-income ratepayers, who are least able to absorb higher water bills and have the most pressing concerns regarding affordability.

- The RI numerator does not include all water costs that users face on utility bills since it only factors in utility operations costs and costs for proposed capital projects, rather than user surcharges or fixed costs included in some rate designs.

- The basis of the 2 percent wastewater RI threshold is “unknown and inherently subjective.” The 1997 guidance did not contain a methodological or theoretical justification for the number. The threshold is not consistent with BLS consumer expenditure data and appears inconsistent with the economic theory that would suggest water and wastewater expenditures must be weighted against other non-discretionary costs (housing, food, healthcare, clothing, energy, transportation) and available discretionary income.

- The static nature of the thresholds ignores critical trends. The fact that neither the 2 percent wastewater nor the 2.5 percent water thresholds have been changed since the 1990’s, while water costs have risen faster than other utility costs, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), and income growth trends, reinforces the impression that the threshold is subjective, is not tied to empirical data, and does not have a framework to adjust to changing real-world dynamics.

Additionally, because the RI component for wastewater is a two-stage process, an inaccurate first-stage RI finding means an FCI assessment will not even take place. Because of that and the above findings, the scope of this report will focus on RI for both water and wastewater.

In discussions with NAPA about the above critiques, the EPA noted that the RI was intended to assess overall system affordability rather than individual household affordability, that it desired a “common starting point” for negotiations between regulators and individual permittees, and that an adjustment to the metrics would increase staff workload by reopening negotiation around existing consent decrees (legal agreements between EPA and permittees regarding actions and timelines required to achieve compliance with CWA and SDWA regulations).57

The EPA also released an updated framework for wastewater affordability in 2014 wherein it acknowledged that financial capability “is on a continuum” and is not best represented by rigid break points or thresholds. It affirmed that the EPA would consider other information presented by permittees not contained in the FCI, such as income distributions by group or geography, poverty rates and trends, population and labor market trends, and extenuating circumstances around bond ratings, among others.58 Critically, however, the updated framework did not change any of the underlying 1997 affordability evaluation processes or thresholds, nor did it comment on the drinking water RI.

EPA’s points may be valid. However, NAPA found stakeholders report that in practice “in certain regions, EPA regional staff, state regulators, and enforcement staff still rely almost exclusively on the 2 percent MHI test… notwithstanding EPA’s view that EPA is providing flexibility to permittees in assessing financial capacity and excessive burden… this is a problem particularly in EPA’s mid-west Region 5 (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan [emphasis added], Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).”59 NAPA points out that the deficiencies in RI and FCI “limit the ability of those metrics to establish an acceptable and equitable common starting point.” Further, localities report that once they use the 2 percent measure, they often feel locked into it from a regulatory perspective or do not understand that they can engage with the EPA for flexibility on mandates (or they lack the technical capacity to do so).

Industry experts, practitioners, federal agencies, academics, government review panels, and even the EPA’s science advisory board all agree that current affordability metrics are inaccurate and should be updated. Accurate measures of affordability are critical for both equity and efficiency in utility cost allocation and rate design.

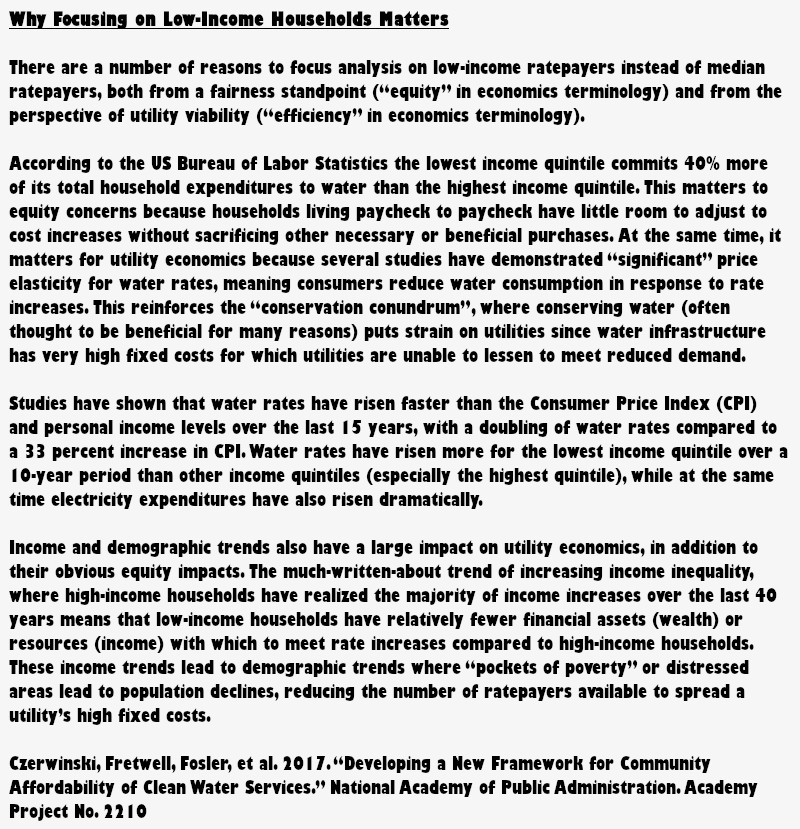

Figure 9: Why Focusing on Low-Income Households Matters

Analysis

This section will propose implementing an alternative metric, demonstrating how the EPA’s current metric misrepresents unaffordability and providing empirical evidence of the actual extent of unaffordability, as well as the distributional impacts of the current rate structures in Southeastern Michigan on various groups. This empirical evidence is then used to inform discussion of policy alternatives to address utility revenue requirements, cost allocation, and capital improvements, as well as funding requirements for customer assistance programs or alternative rate designs in the Alternatives section.

Methodology

This analysis identifies and quantifies the gap in the measurement of affordability issues by first applying EPA’s metrics to GLWA, a large and complex system which serves a diverse population, and then applying a two alternative metrics. The ramifications of this gap are then analyzed in the context of local affordability programs and future capital expenses, noting how under-estimation of affordability by current metrics negatively impacts decisions around funding for assistance programs and distorts cost allocation and revenue recovery inputs for utility capital planning and rate design. GLWA wholesale customers (all communities besides Detroit) and DWSD retail (Detroit) customers are analyzed separately to acknowledge the administrative regime stemming from the GLWA/DWSD lease and operation agreements. This analysis shows meaningful outcomes that should inform GLWA and DWSD-R customer practices—most notably the pursuit of an effective, robust affordability plan or alternative rate structure. Policy alternatives and recommendations based on the identified gap and estimated needs for both low-income ratepayers and utility planning are proposed.

Choice of Alternative Metrics

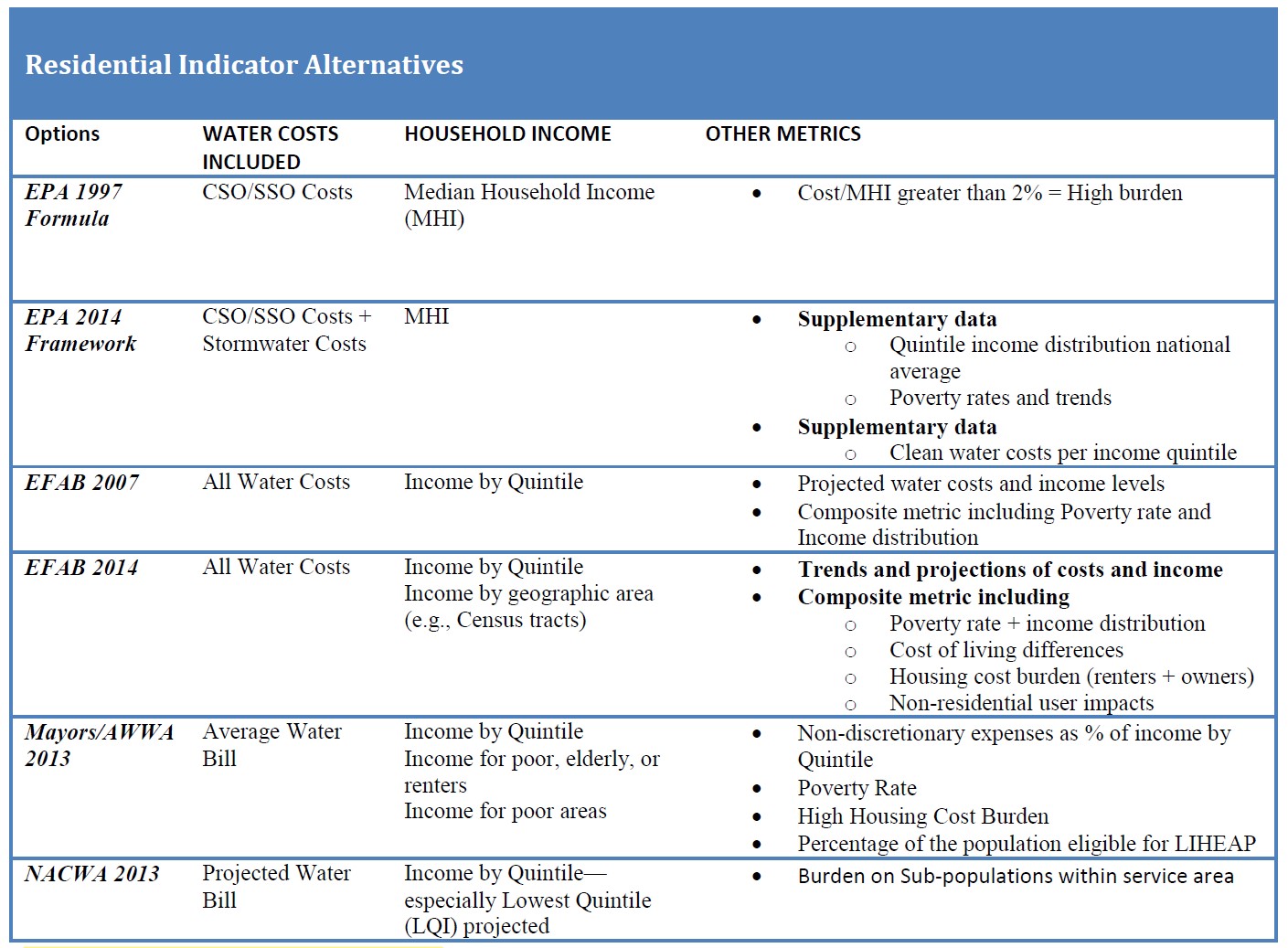

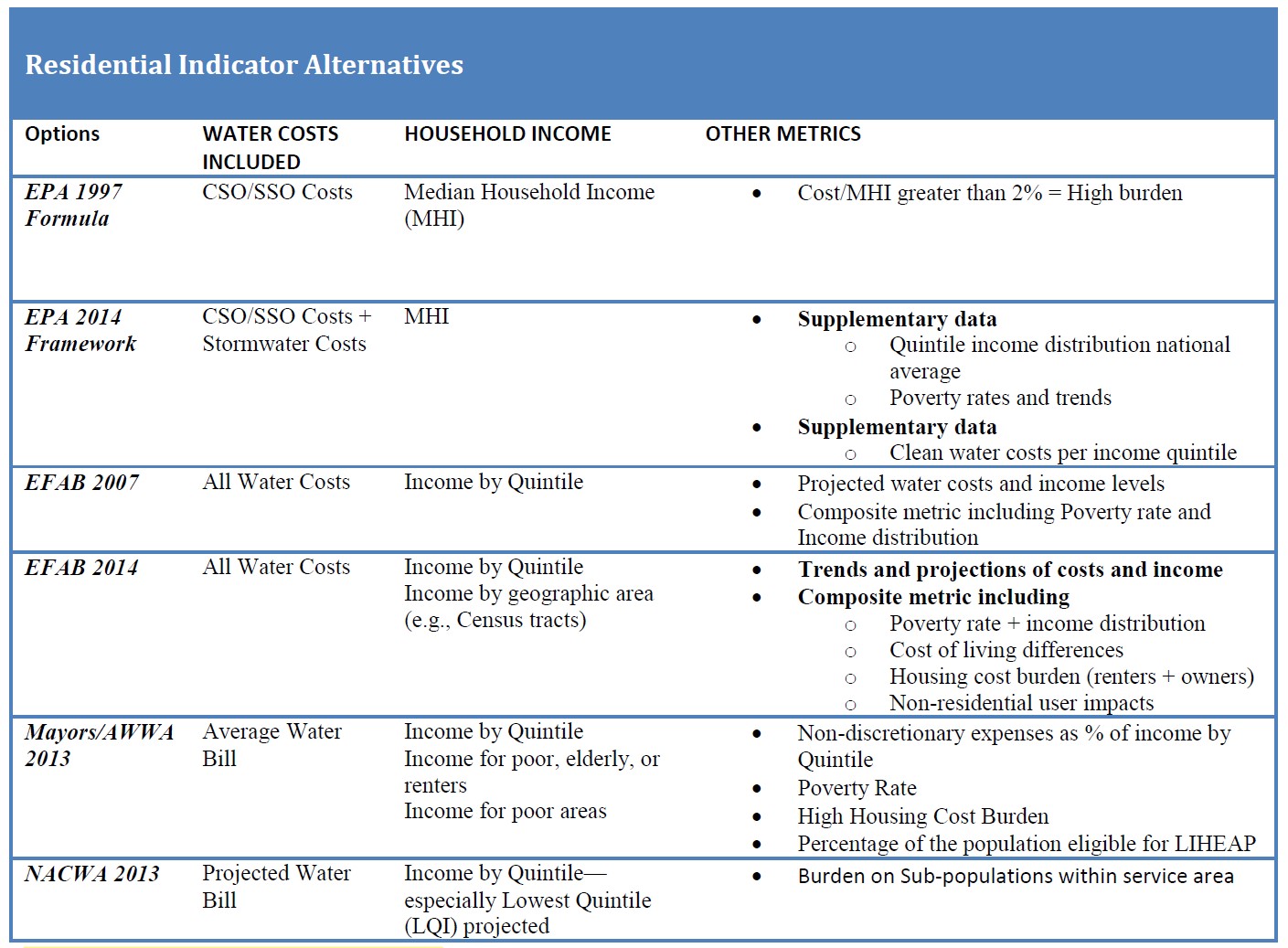

A number of alternative metrics have been proposed by both academics and practitioners. Figure 2 from NAPA’s meta-analysis summarizes a selection of proposals:

Figure 10: Residential Indicator Metric Alternatives

Image source: Czerwinski, et al., 2017.

Most proposals attempt to gain a clearer picture of user affordability by using income quintile instead of MHI. Other proposals not mentioned in the NAPA table suggest using local community MHI rather than EPA’s nationwide small system MHI or utility-wide MHI to identify clusters of unaffordability missed by larger-jurisdiction MHI.60 Multiple proposals use the average ratepayer water bill rather than system costs to more directly compute user affordability before analyzing utility financial capability (acknowledging the interconnection between the two). Finally, most proposals include supplemental contextual information such as trends, poverty rates, housing cost burden, and analysis of sub-populations within a utility service area.

The alternative metrics used here will follow NAPA’s recommendations of simplicity, readily available public data sources, and applicability for comparative analysis among different utilities (see Appendix 2).61 This is consistent with the desire for this study’s metrics to be replicable by multiple stakeholders—from the government to community members. It will also follow recommendations to include drinking water and wastewater costs together, to focus on low-income users rather than median users, and to identify the size of the population of vulnerable users relative to the utility’s total ratepayer base.62

Implementation of Two Alternative Metrics

The alternative metrics in this analysis will be done in two rounds to illustrate the extent that EPA’s current metric misrepresents affordability. Both will focus on place-based analysis, which was consistently emphasized during NAPA’s stakeholder engagements63 , as opposed to EPA’s current use of aggregated MHI—an approach that is not sensitive to local variation.

In this study, we first measure affordability using the EPA’s metrics as interpreted by the Affordability Assessment Tool for Federal Water Mandates published by the American Water Works Association, United States Conference of Mayors, and Water Environment Federation.64 They describe the EPA’s wastewater RI as “average per household cost of wastewater bills relative to median household income in the service area”65 rather than strictly adhering to the EPA’s 1997 guidance that describes costs as a function of annual operations and maintenance expenses, annual debt service, residential share of costs, and number of households.66 Similarly, the Affordability Assessment Tool interprets the EPA’s drinking water RI to include annual household bills as the cost indicator. This technique is also among the metric options recommended by the NAPA report.

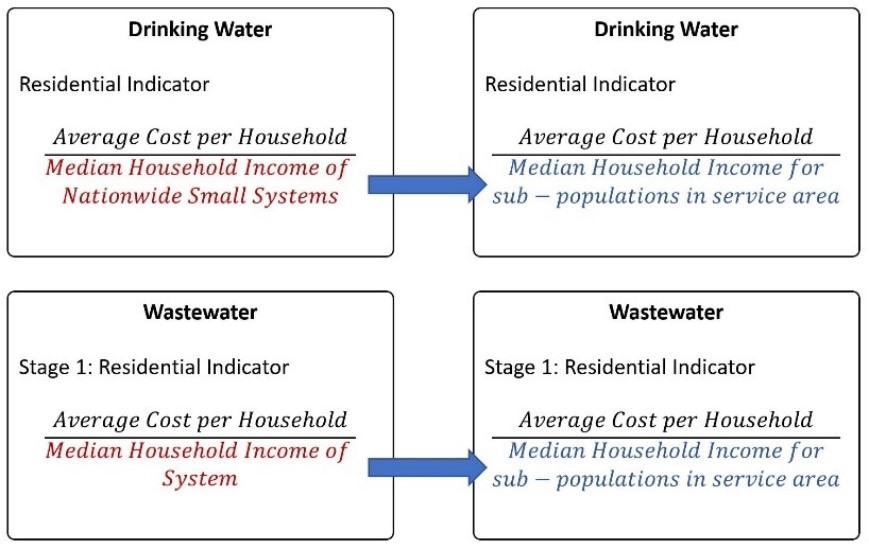

Figure 11: The EPA metric and this study’s conservative alternative

The first alternative metric in this study will change the EPA metric’s numerator from “selected operations costs” and “planned upgrade costs” to actual costs faced by households by substituting total household bills (water, wastewater, and combined) based on average usage volume. This shifts the focus from theoretical cost allocation to actual average costs faced by households. The first alternative metric will also change the denominator from national small-system MHI for water and system-wide MHI for wastewater to local MHI for sub-populations within the service area for both water and wastewater. This shifts the focus from aggregated measures to place-based analysis that more accurately represents utility users and gives a sense of the size of vulnerable users relative to total ratepayer base. This amounts to a conservative estimate of affordability that does not radically challenge the EPA’s chosen threshold values and is not responsive to the much-agreed-to need to focus on lower-income households. This setup biases the specification of the alternative metric in favor of the status quo tendency to mask unaffordability, meaning that if unaffordability is found, then the extent of those issues are severe enough to show through a model prone not to reveal it. Accordingly, findings from applying the second alternative metric are more believable because the results do not disappear if preferred modeling assumptions are removed.67

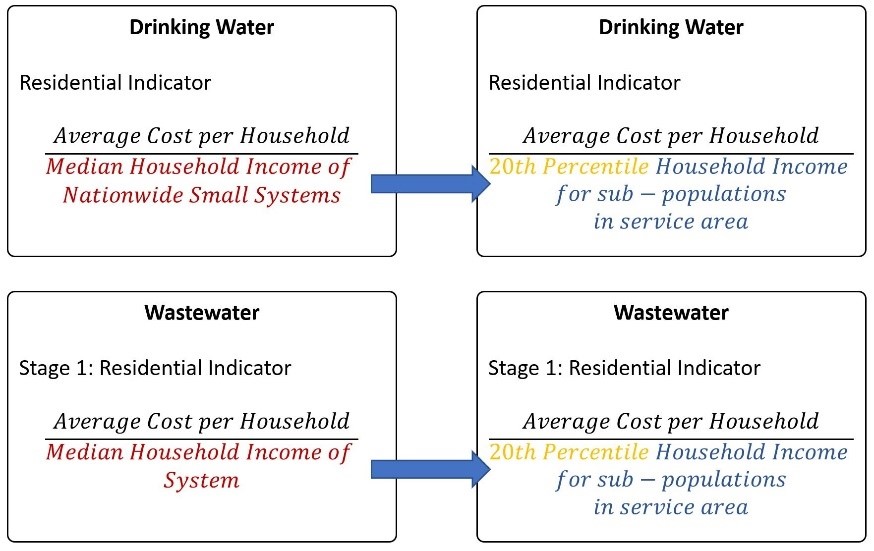

Figure 12: The EPA metric and this study’s realistic alternative

The second alternative metric will again change the numerator in the same way as the first round. The denominator, however, will change from MHI for sub-populations to income of the upper bound sub-populations to income of the upper bound of the first quintile (equivalent to the twentieth percentile) for those sub-populations. This refocuses the income analysis away from the unrepresentative median and instead to what is often considered the lower boundary of the middle class68 to better reflect the set of individuals who are most sensitive to rate increases. This sensitivity is defined as those subjected to greater harm from rate increases but also more likely to adjust consumption behavior, the first being critical for equity analysis and the second being critical for efficiency analysis. (See Feature Box at the end of the Background section)

Data Sources

Demographic and economic data for primary affordability calculations come from the United States Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) 2016 five-year estimates. Spatial data comes from the United States Census Bureau Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing (TIGER) products. Demographic and economic data for time series and trend analysis come from ACS one-year, three-year, and five-year estimates, with decennial census as needed. Retail water and sewer rate information was obtained from GLWA, DWSD, and individual cities, towns, townships, and charter townships. When rate information was not available online, it was obtained via telephone from local officials. System usage and capital financial data were obtained from GLWA and DWSD.

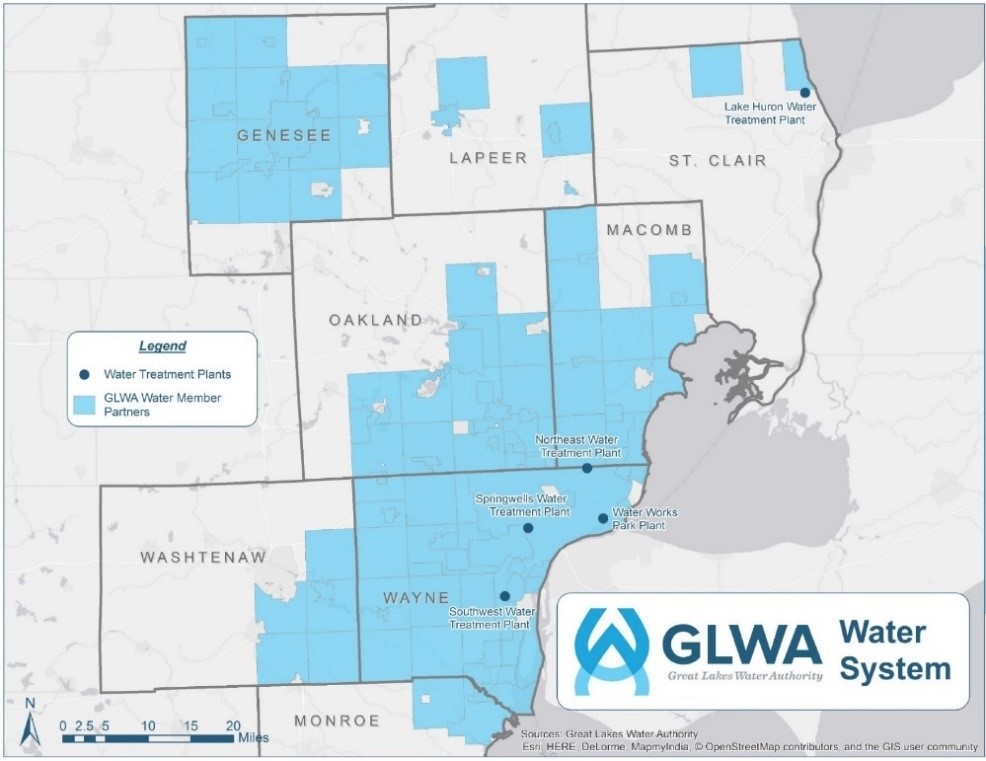

Great Lakes Water Authority Service Area

The GLWA service area (including the City of Detroit and leased DWSD infrastructure) is large and complex, spanning 1,069 square miles, 2,700 miles of transmission lines, five water treatment plants, and 19 booster pump stations for water delivery, as well as three interceptors, eight combined sewer overflow facilities, and five pump stations for wastewater management.69 The water system includes 127 member partners that purchase water from GLWA representing 119 individual communities.70 The wastewater system serves 87 member partners representing 76 individual communities.71

Figure 13: GLWA Water Service Area

Image source: GLWA Year in Review, 2017

To apply place-based affordability metrics, the complex GLWA service area was created according to census geographical units. This analysis uses county subdivisions (census code 060) for community-to-community analysis, since Michigan is one of 12 states where county subdivisions are legal entities—as opposed to statistical areas derived by census bureau staff—that serve as local governments (called Townships or Charter Townships) similar to small cities or towns.72 This means that census cities, towns, townships, and charter townships directly correspond to legal cities, towns, townships, and charter townships that enter into wholesale utility agreements.

Analysis of economic and demographic factors takes place at a smaller resolution, using individual census tracts (census code 140) to identify more nuanced differences among groups within individual communities, akin to neighborhoods. Census tracts within the GLWA service area were computed using the MABLE/GeoCorr14 geographic correspondence engine.

Computation of Average Bills

Average per capita water consumption in the United States is estimated to be between 2,400 and 3,000 gallons per month.73 Average usage for the GLWA service area was computed using monthly service volume within Detroit (the jurisdiction with the clearest reported monthly service volume) divided by the number of households and the average number of individuals per household.74 The resulting per capita estimate was 2,640 gallons per month, squarely within the national average. Total average household monthly usage given the average family size of 2.675 is 6,864 gallons. This is roughly confirmed across GLWA, which reports average monthly usage for a family of three as 7,000 gallons.76

That monthly average was combined with individual community water rates per unit, wastewater rates per unit if applicable, fixed charges (water and wastewater), special charges (water and wastewater), and number of billing periods per year to compute average annual bills broken out by water and wastewater (see Appendix 1 for details). When billed by meter size, 5/8 connector (or smallest available) was chosen, as most residential meters are this size.

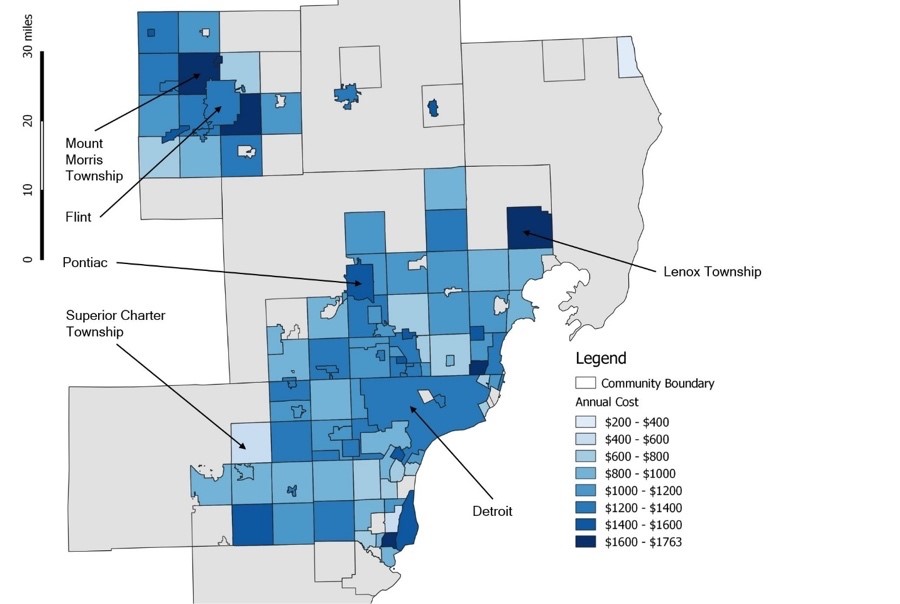

The image below shows average annual household water and wastewater bills for each community served by GLWA.77

Figure 14: Average Annual Household Water and Wastewater Bills (6,864 Gallons per Month per household)

Average total annual bills for communities within GLWA range from $492.80 to $1,762.86, with wastewater costs typically $32.23 higher than water costs, although a portion of that for some communities could be attributable to wastewater infrastructure outside of GLWA management (see Appendix 3). The average annual total bill for Detroit is $1,246.51, with wastewater comprising 63 percent of that total bill. Aside from a cluster of relatively high costs in and around Flint, as well as a cluster of relatively lower costs south of Detroit, there are no clear spatial patterns to costs. Figure 15 below is a scatter plot showing annual water costs on the y-axis, median household income on the x-axis, and with each point representing a community scaled by the number of households.

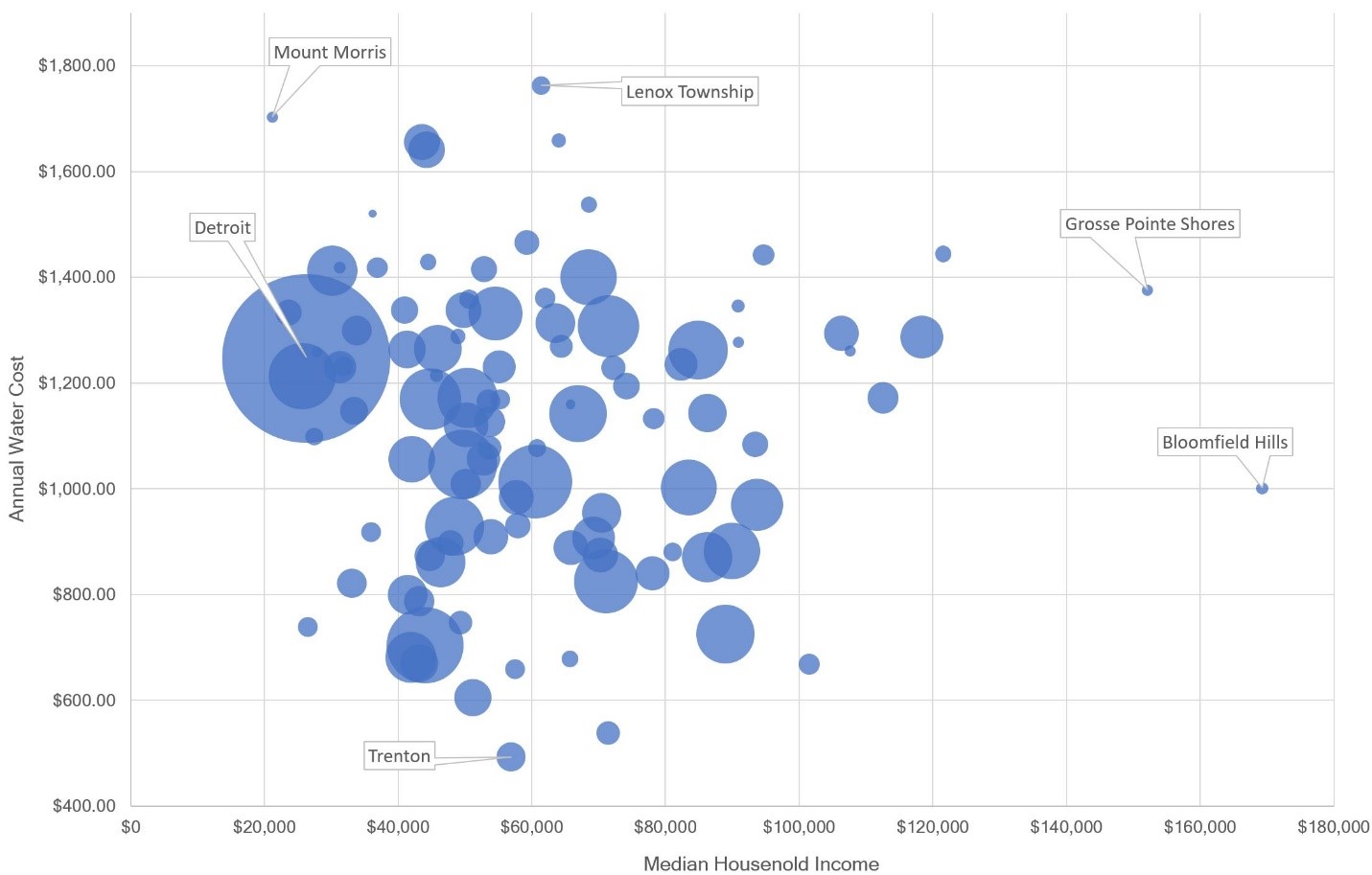

Figure 15: Scatter Plot of Annual Water Costs, Median Household Income, and Number of Households

Image source: US Census, Individual local governments, author calculations

Aside from a few outliers within MHI, annual water costs, and number of households, there are no clear relationships or trends between any of the dimensions. If there were relationships between MHI, annual water costs, and/or number of households, a more linear pattern would emerge in the scatter plot.

Community Economic Characteristics

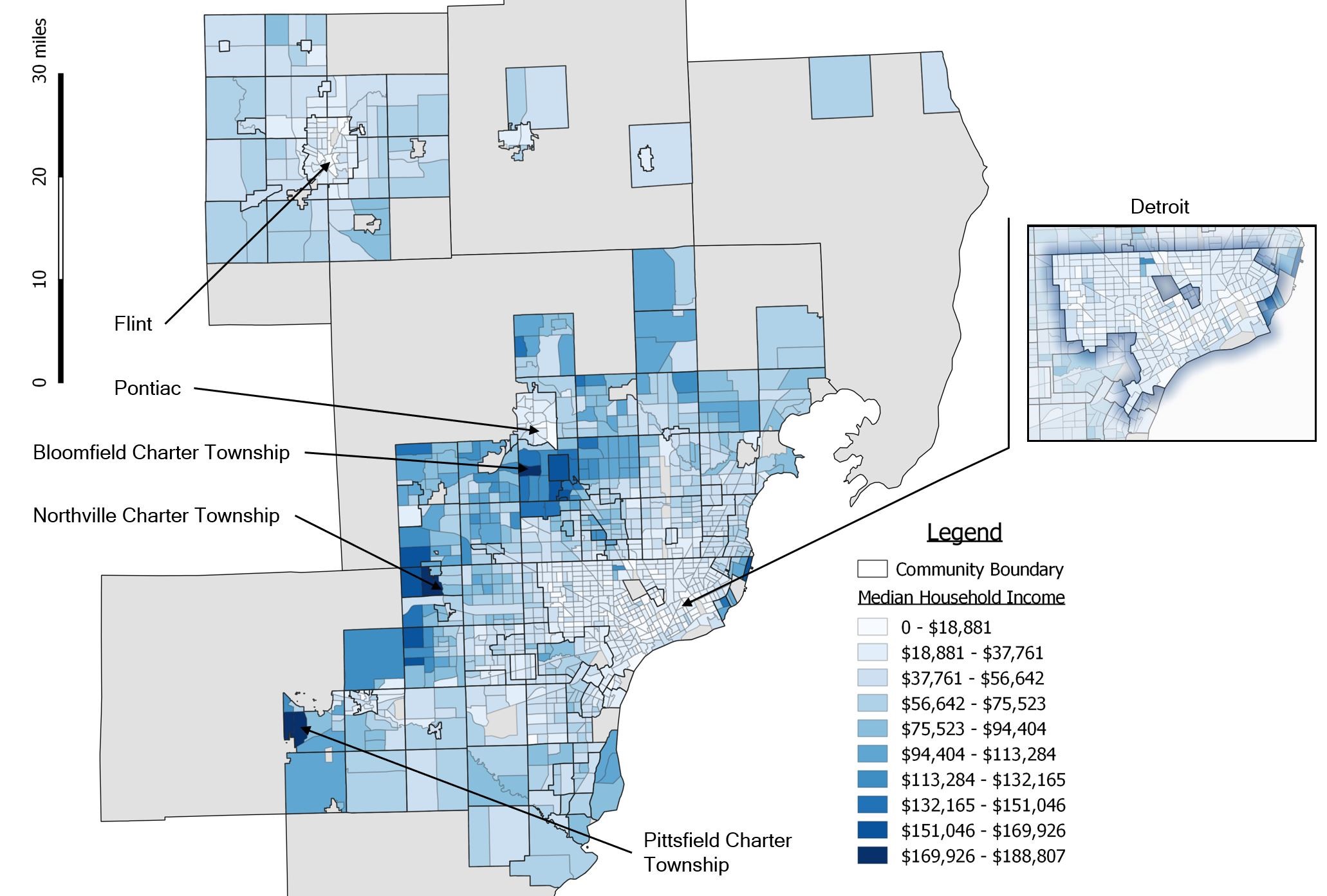

Median Household Income across the GLWA service area is represented below in Figure 16:

Figure 16: Median Household Income by Census Tract, 2016

Image source: US Census Bureau

These data show patterns of low-income households in urban areas such as Detroit, Flint, and Pontiac, with higher-income areas encompassing the suburban areas between the urban centers, such as Bloomfield Township, Pittsfield Township, and Northville Township. Part of the reason for such patterns include the well-reported economic decline of Detroit and similar urban centers, as mirrored in unemployment rates seen in Figure 17 below.

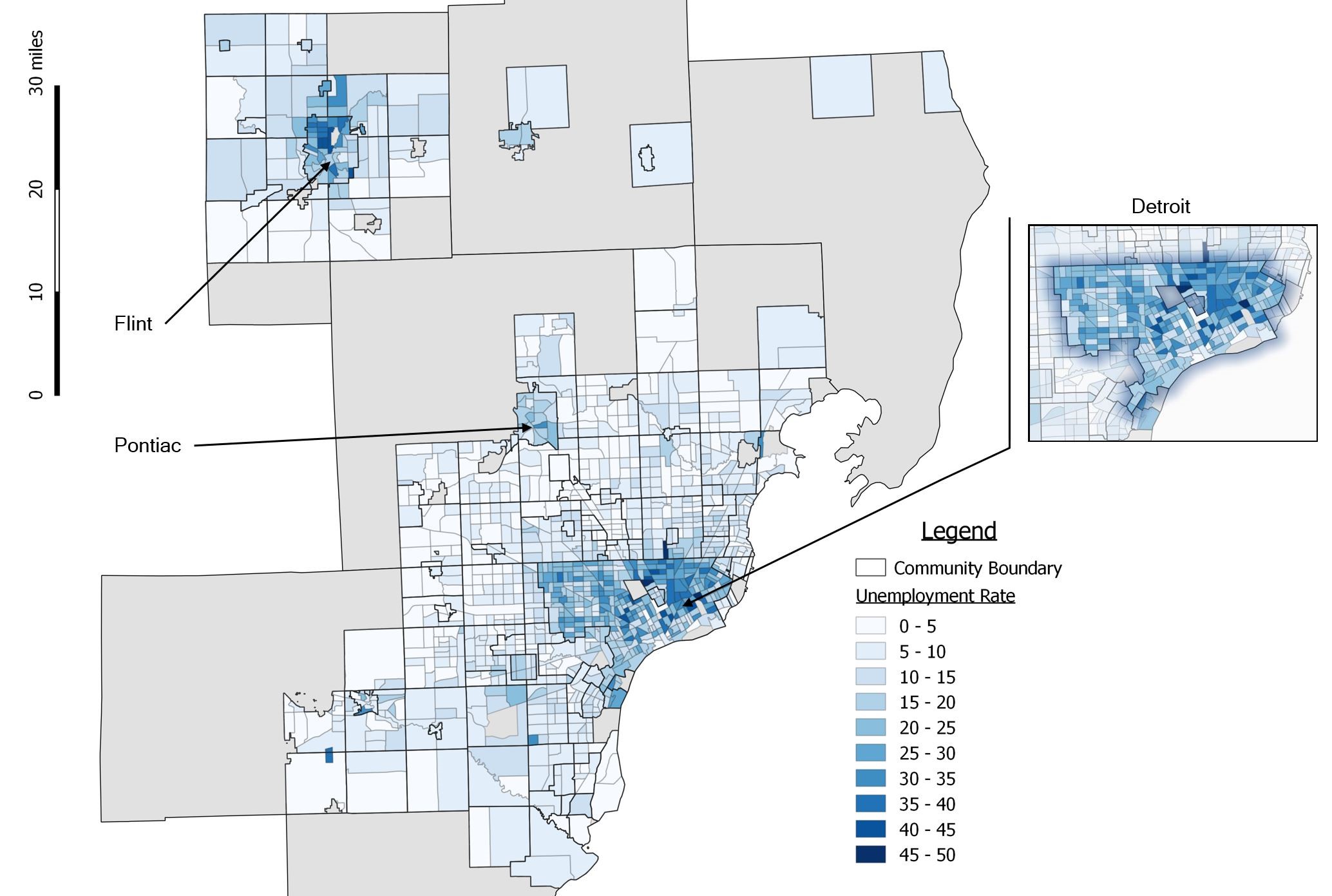

Figure 17: Unemployment Rate by Census Tract, 2016

Image source: US Census Bureau

The data represented on these maps, and the map of annual water costs, are combined as inputs into the metric calculations shown in the results section below.

Results

Affordability Results of EPA Metric

Recall that the EPA’s RI for drinking water uses the median household income of nationwide small systems and an unaffordability threshold of 2.5 percent, while the RI for wastewater uses MHI for the system and an unaffordability threshold of 2 percent.

Individual community MHI within GLWA has a wide range, with a minimum of $21,196 and a maximum of $169,265. The EPA’s 1997 guidance instructs system-wide MHI be calculated from a weighted average that scales each community’s MHI by the proportion of total households it represents. GLWA’s weighted average MHI is $60,570.17, while Detroit’s MHI is $26,249.

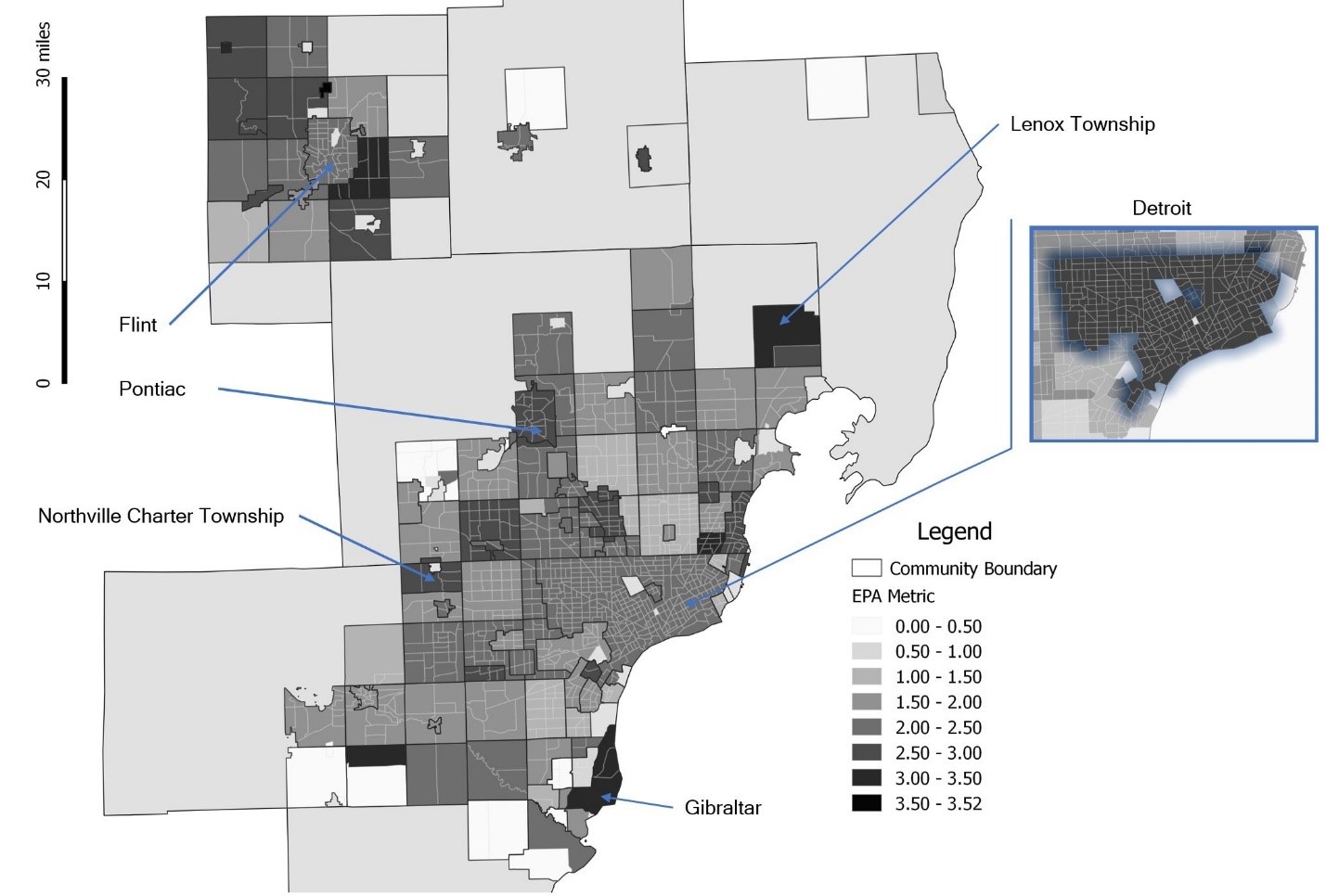

Combining these inputs into the RIs yields an average combined water and wastewater result of 2.20 percent, a water result of 1.25 percent, and a wastewater result of 0.96 percent. The highest result was 3.52 percent, with the lowest being 0.97 percent (See Appendix 4 for full table), as seen in Figure 18.

Figure 18: EPA Metric Results

Image source: US Census Bureau, individual local governments, author calculations

Detroit, although found to have a higher combined water/wastewater percentage, is still deemed affordable at 2.35 percent, with water and wastewater individually at 1.05 percent and 1.29 percent, respectively.

Under the EPA’s current metric, no community or neighborhood is found to be unaffordable either in the total bill or water/wastewater component part.

Affordability Results of Two Alternative Metrics

Specification 1: Conservative Estimate (Local MHI)

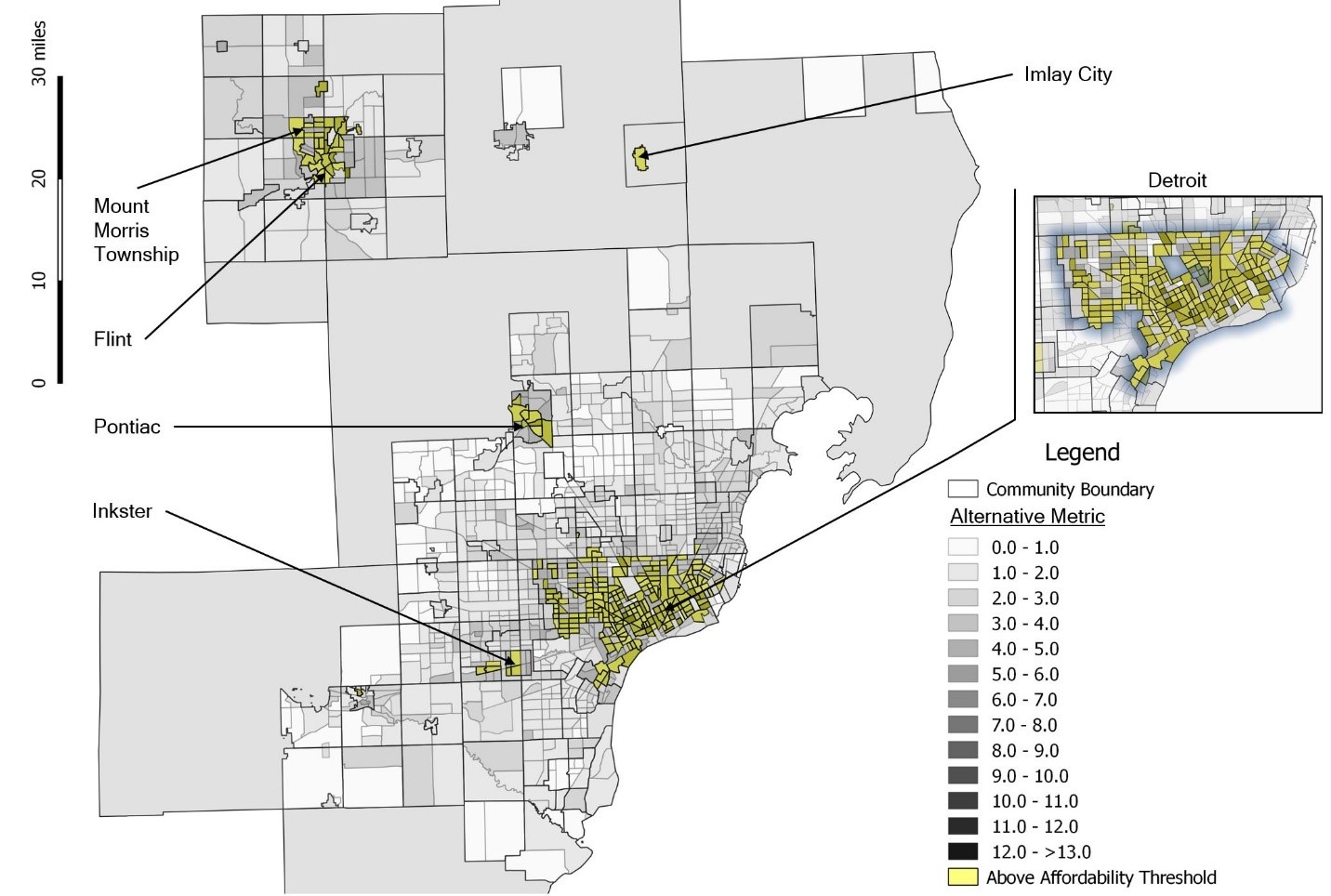

This conservative specification of the alternative metric changes the EPA metric’s denominator from national small-system MHI for water and system-wide MHI for wastewater to local MHI for sub-populations within the service area for both. This amounts to a conservative estimate of affordability that does not radically challenge the EPA’s chosen threshold values, or even use the much-agreed-on need to focus on lower-income households. Since this model is conservative, a finding of unaffordability here means that the true extent of unaffordability is severe enough to show through a model that is still biased against revealing it. Figure 19 shows the results of the conservative alternative metric and highlights census tracts that breach the 4.5 percent combined water and wastewater indicator in yellow.

Figure 19: Conservative Alternative Metric Results (4.5 percent Combined Water & Wastewater Threshold)

Under this specification of the metric, unaffordability begins to appear at MHI below $31,300, as seen in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Communities Below $31,300 Median Household Income

| Name | Local MHI | Annual Water Costs78 | EPA Metric | Alternative Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imlay City | $31,287 | $1,418.40 | 2.87 | 4.53 |

| Inkster79 | $31,285 | $1,230.58 | 2.29 | 3.93 |

| Pontiac | $30,152 | $1,412.52 | 2.81 | 4.68 |

| Royal Oak Township | $27,837 | $1,258.80 | 2.36 | 4.52 |

| River Rouge | $27,463 | $1,098.79 | 2.09 | 4.00 |

| Ecorse | $26,496 | $738.53 | 1.44 | 2.79 |

| Detroit | $26,249 | $1,246.51 | 2.35 | 4.75 |

| Flint | $25,650 | $1,213.53 | 2.45 | 4.73 |

| Hamtramck | $23,609 | $1,333.36 | 2.5 | 5.65 |

| Mount Morris | $21,196 | $1,702.71 | 3.52 | 8.03 |

It is notable that not only low-income urban areas face unaffordability issues. While the core urban centers and their neighboring communities of Mount Morris, Hamtramck, Ecorse, and River Rouge face unaffordability driven by a mixture of low incomes and high costs, the suburban communities of Inkster and Imlay City face very similar issues. Although they have the highest incomes of the locations that rise above the 4.5 percent threshold, they are only barely above 150 percent of the federal poverty level ($30,240 for a family of three), which is a common threshold for some public assistance benefits.80 Additionally, the communities of Lapeer, Montrose, Melvindale, Eastpointe, and Almont each face partial affordability for water or wastewater (rising above the threshold value for one of the two), even though their MHI rises above $31,300 (See Appendix 4 for full table).

In Detroit, 272,774 households reside within census tracts whose RI breaches the 4.5 percent threshold, representing households at risk for unaffordability. Of those households, 72,185 had annual household incomes under $29,999,81 making them extremely likely to face unaffordability. Within the rest of GLWA, 59,381 households are at risk, and 35,864 are extremely likely to face unaffordability.

When the metric is tailored to actual on-the-ground economic characteristics, unaffordability issues become clear, even under modeling assumptions biased against finding unaffordability.

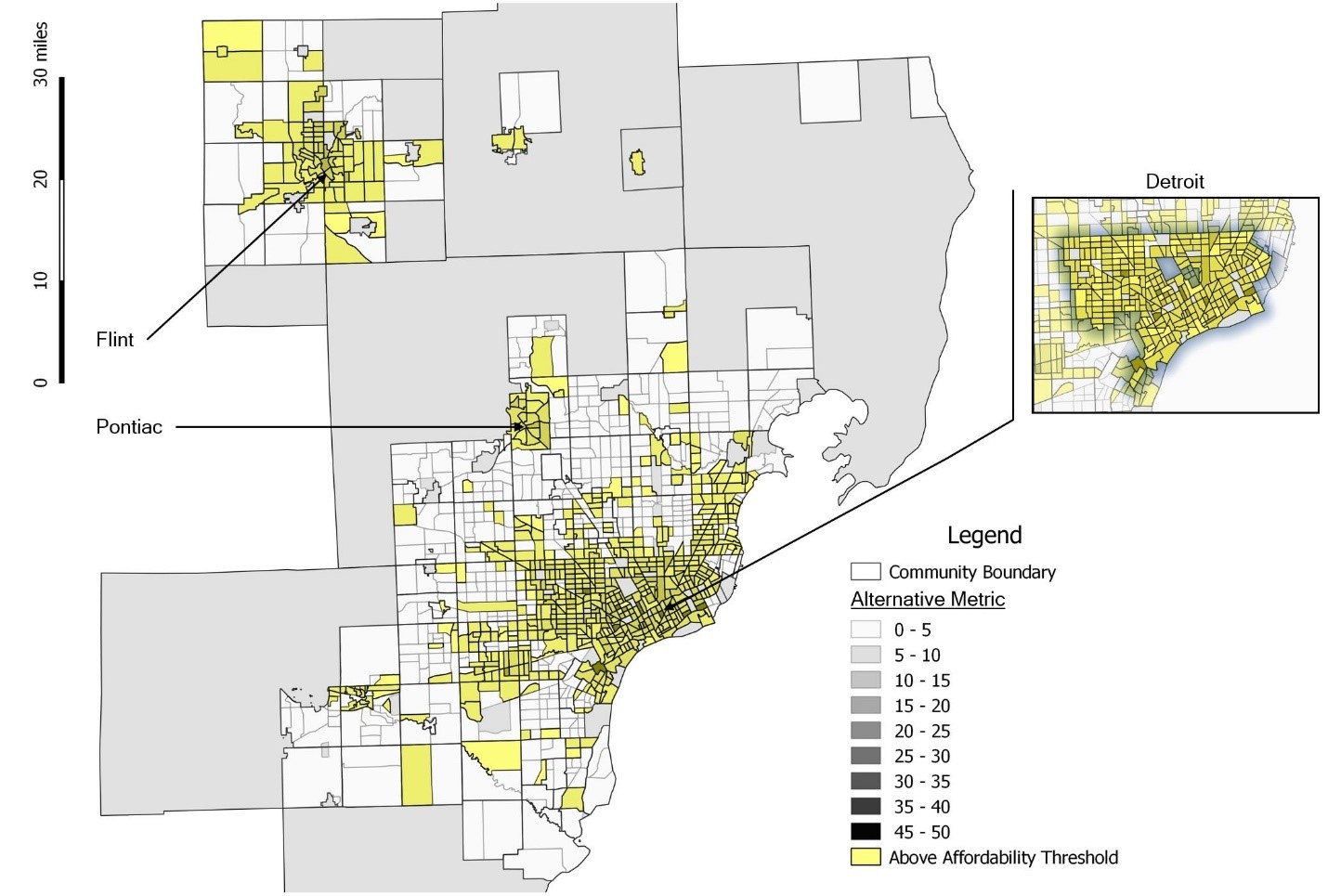

Specification 2: Realistic Estimate (Local MHI and Focus on twentieth Income Percentile)

This realistic specification of the model makes the same changes to introduce local data for place-based analysis that the conservative specification made, but also shifts the focus of the denominator to the upper bound of the first quintile of the income distribution (twentieth percentile) as recommended by NAPA. This amounts to a more realistic representation of affordability issues that reflect struggles faced by households and also provides more accurate inputs for utility financial planning based on actual customer ability to pay. Figure 20 shows the results of the realistic alternative metric and again highlights census tracts that breach the 4.5 percent combined water and wastewater indicator in yellow.

Figure 20: Realistic Alternative Metric Results (4.5 percent Combined Water & Wastewater Threshold)

Image source: US Census Bureau, individual local governments, author calculations

It is worthwhile to note that a spatial component to the analysis is important since it reveals additional relationships that most tables alone do not. When communities that tip affordability thresholds are mapped, it becomes clear that “pockets of poverty”82 extend beyond impoverished urban areas, as well as smaller neighborhood-level pockets of unaffordability within communities.

Under the realistic alternative metric unaffordability issues again begin to arise around roughly $30,000 annual household income (except for Lenox Township, which has the highest annual costs of all communities). However, many more communities have twentieth percentile incomes below this level. Whereas the conservative metric found six communities to have RIs above the threshold, the realistic metric found 45 to be above the threshold. Table 2 below shows the upper five and lower five communities ranked by twentieth percentile income from this group (see Appendix 4 for full table):

Table 2: Selected Communities Above 4.5 percent RI Threshold Under Realistic Metric Specification

| Name | 20th Percentile Income | Annual Water Costs83 | EPA Metric | Alternative Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenox Township | $33,727 | $1,762.86 | 3.27 | 5.23 |

| Royal Oak | $30,520 | $1,400.01 | 2.57 | 4.59 |

| Clawson | $28,345 | $1,465.39 | 2.73 | 5.17 |

| Gibraltar | $27,458 | $1,658.89 | 3.15 | 6.04 |

| Montrose Township | $26,232 | $1,288.17 | 2.64 | 4.91 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Inkster | $10,351 | $1,230.58 | 2.29 | 11.89 |

| Flint | $9,897 | $1,213.53 | 2.45 | 12.26 |

| Hamtramck | $9,818 | $1,333.36 | 2.5 | 13.58 |

| Detriot | $9,574 | $1,246.51 | 2.35 | 13.02 |

| River Rouge | $9,435 | $1,098.79 | 2.09 | 11.65 |

Under this specification, the previous trends around urban centers and their immediate neighbors remain, however, many more suburban communities—including communities far from urban centers—are found to face potential affordability issues since the metric is now calibrated to focus on the segment of the customer base where costs are more acutely felt.

In Detroit, 104,181 households are located within census tracts whose RI breaches the 4.5 percent threshold and have annual household incomes under $29,999, while the rest of GLWA has 204,308 households that fall under the same criteria. It is also important to note that although the number of communities found to face unaffordability pressures jumps by 650 percent, the number of households within each community represented in this metric specification only increases by 470 percent for GLWA and 44 percent for Detroit.84 This is because the conservative specification uses median household income, under which half of all households fall, whereas the realistic specification uses the upper bound of a single quintile for household income, which represents one-fifth of all households. Thus, although the geographic spread of unaffordability grows with this specification of the metric, the absolute number of households does not grow at the same rate.

This is precisely what this specification of the metric is meant to do: reveal the actual areas of unaffordability that are masked by aggregate median measures, but not to inflate the scale of the problem. The metric should reveal the extent of unaffordability pressures on households susceptible to such pressures but remain useful as a tool to utilities and regulators.

The EPA metric attempts to simplify review by using aggregate measures, but has been shown to mask unaffordability. At the same time, more accurate measures are shown not to be unnecessarily complex. Further, the accurate measures can be simplified in a number of ways as a final step to get a single system-wide number as an input for planning purposes. This feature was the original intent with the EPA’s original specification of the metric.85 For example, the new final stage of the RI could be the proportion of census tracts or communities system-wide that face unaffordability issues above the 4.5 percent threshold. This would essentially turn the current RI (after the adjustments to local MHI and twentieth percentile income) for each community into a first stage matrix that is then condensed into a new ratio of unaffordable census tracts to total census tracts as a final single-number output. This achieves the dual goal of making sure the metric accurately reflects the real-world information it is trying to convey, while still being simple enough to use as an input into complex planning models without being a burden on limited utility, community, or regulator staff resources.

When the metric is tailored to on-the-ground economic characteristics and the segment of the population most sensitive to unaffordability, the true scope of the problem is revealed and utilities are better able to plan accordingly in revenue requirement, cost allocation, and capital improvement planning calculations.

Distributional Impacts of Affordability Challenges

In addition to economic, cost, and population characteristics, it is important to know the demographic characteristics of populations facing unaffordability, especially if those populations are vulnerable in certain ways.86 A nationwide study of affordability found that census tracts with median incomes below $32,000 have higher percentages of disabled people, higher unemployment rates, higher levels of public assistance income, a higher incidence of sole female heads of household, larger percentages of minority residents, and lower rates of health insurance.87 87 Local stakeholders who have addressed affordability in southeastern Michigan have pointed to the lack of research on these particular issues, which this study attempts to rectify.88

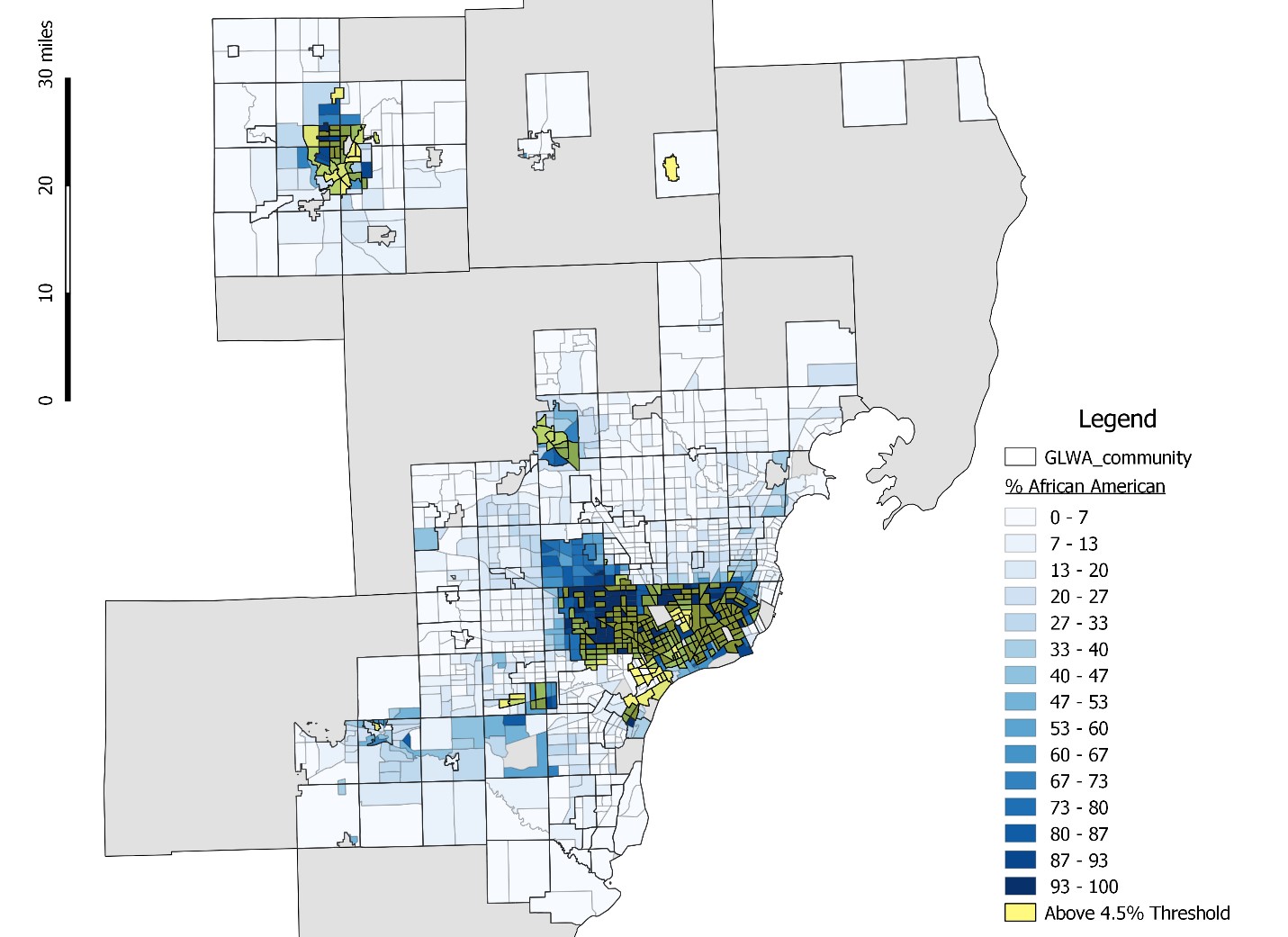

As can be seen in the figures below, the nationwide trends are reflected in the Michigan data. Figure 21 shows the percentage of African Americans by census tract with tracts from the conservative specification over the 4.5 percent RI threshold (i.e., the extreme cases of unaffordability) highlighted in yellow. The correlation between the two is striking.

Figure 21: Census Tracts by Percent African American and Above 4.5 percent RI Threshold

Image source: US Census, author calculations

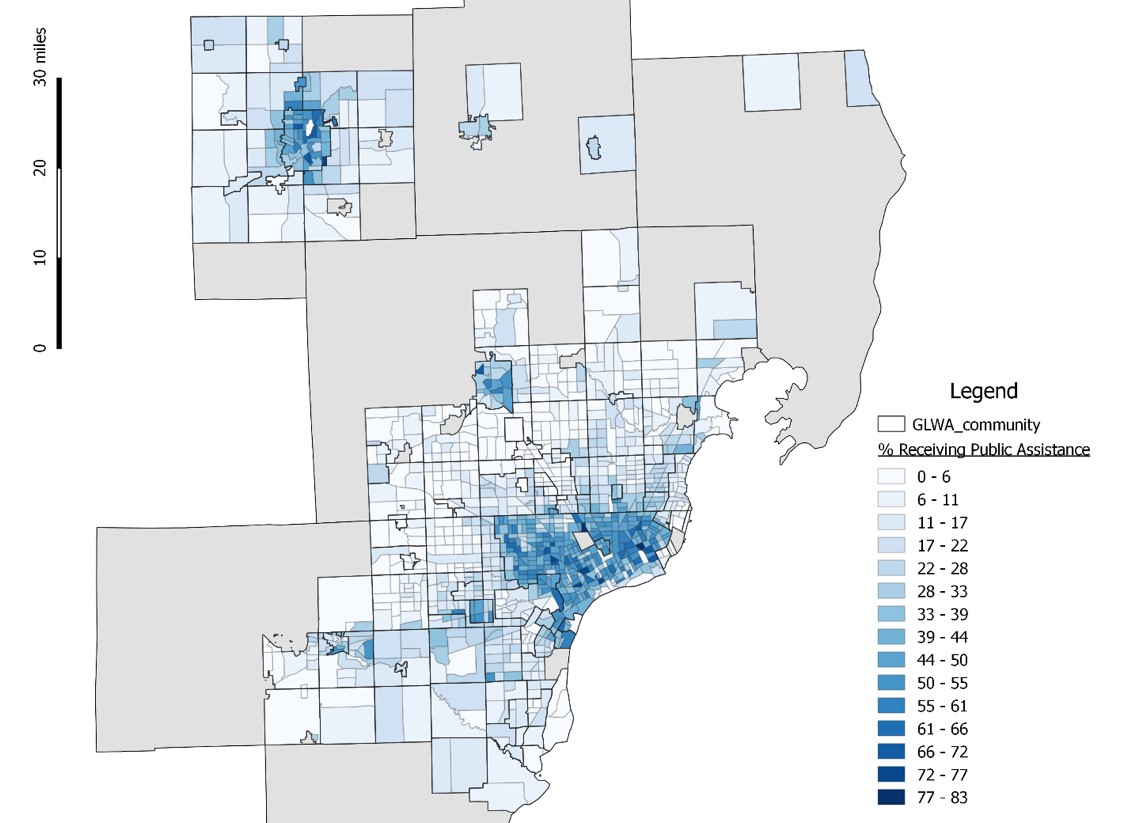

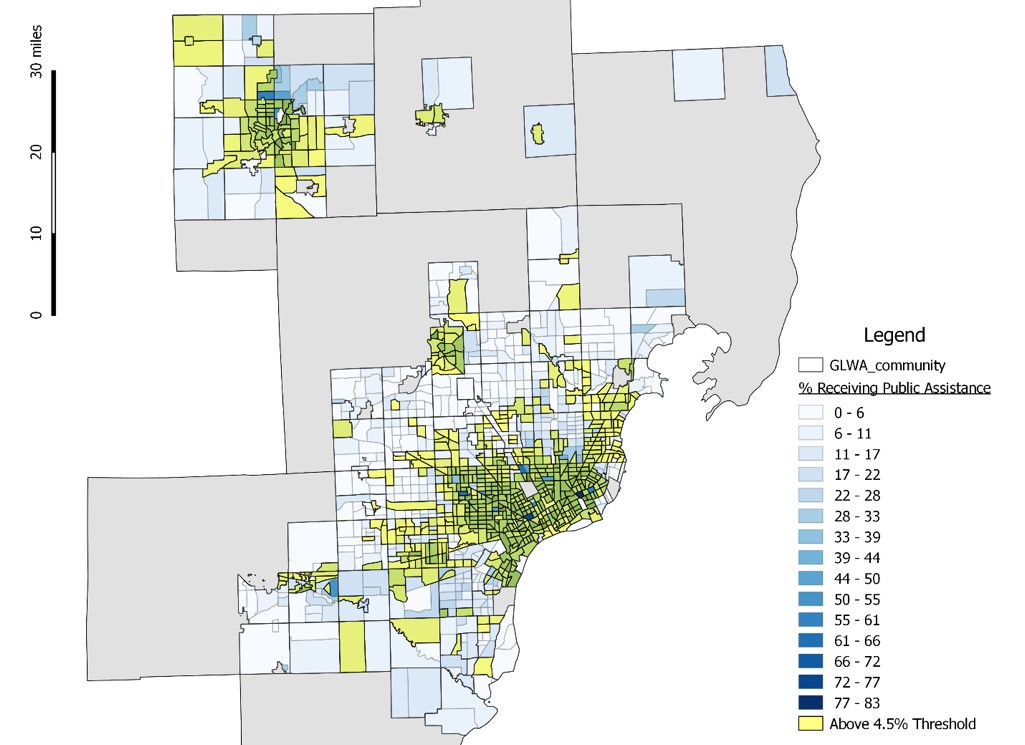

Figures 22 and 23 below show the extent of public assistance89 used within census tracts and the census tracts that rise above the 4.5 percent affordability threshold evaluated at the twentieth percentile.

Figure 22: Census Tracts by Percent Receiving Public Assistance

Image source: US Census, author calculations

Figure 23: Census Tracts by Percent Receiving Public Assistance and Above 4.5 percent RI Threshold

Image source: US Census, author calculations

Again, the connection between the two is visible, with the highest rates of public assistance occurring in and around the metro centers of Detroit, Pontiac, and Flint, but also spreading to the surrounding suburbs, especially towards the southwest, alongside the tracts that fall above the 4.5 percent threshold.

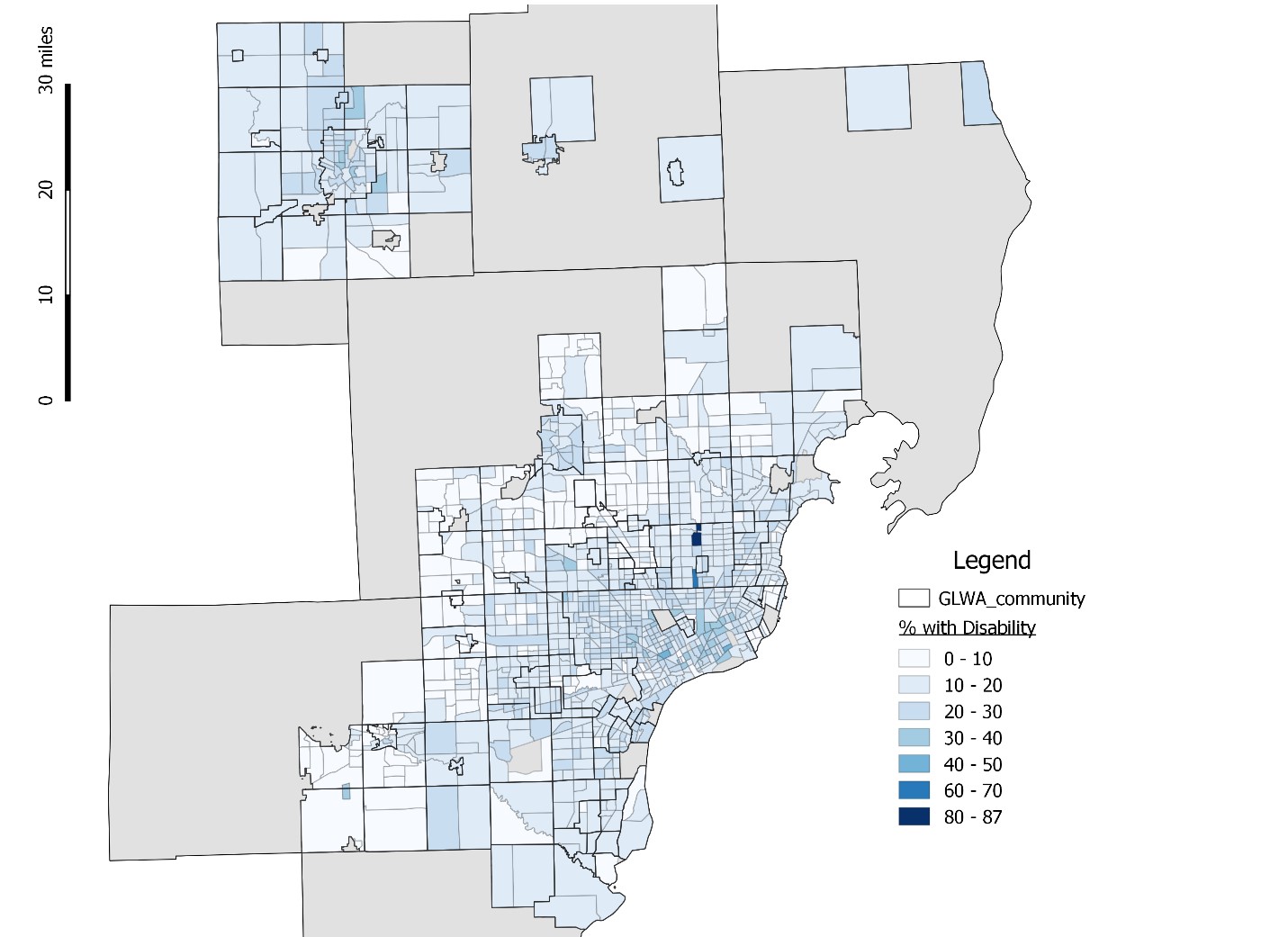

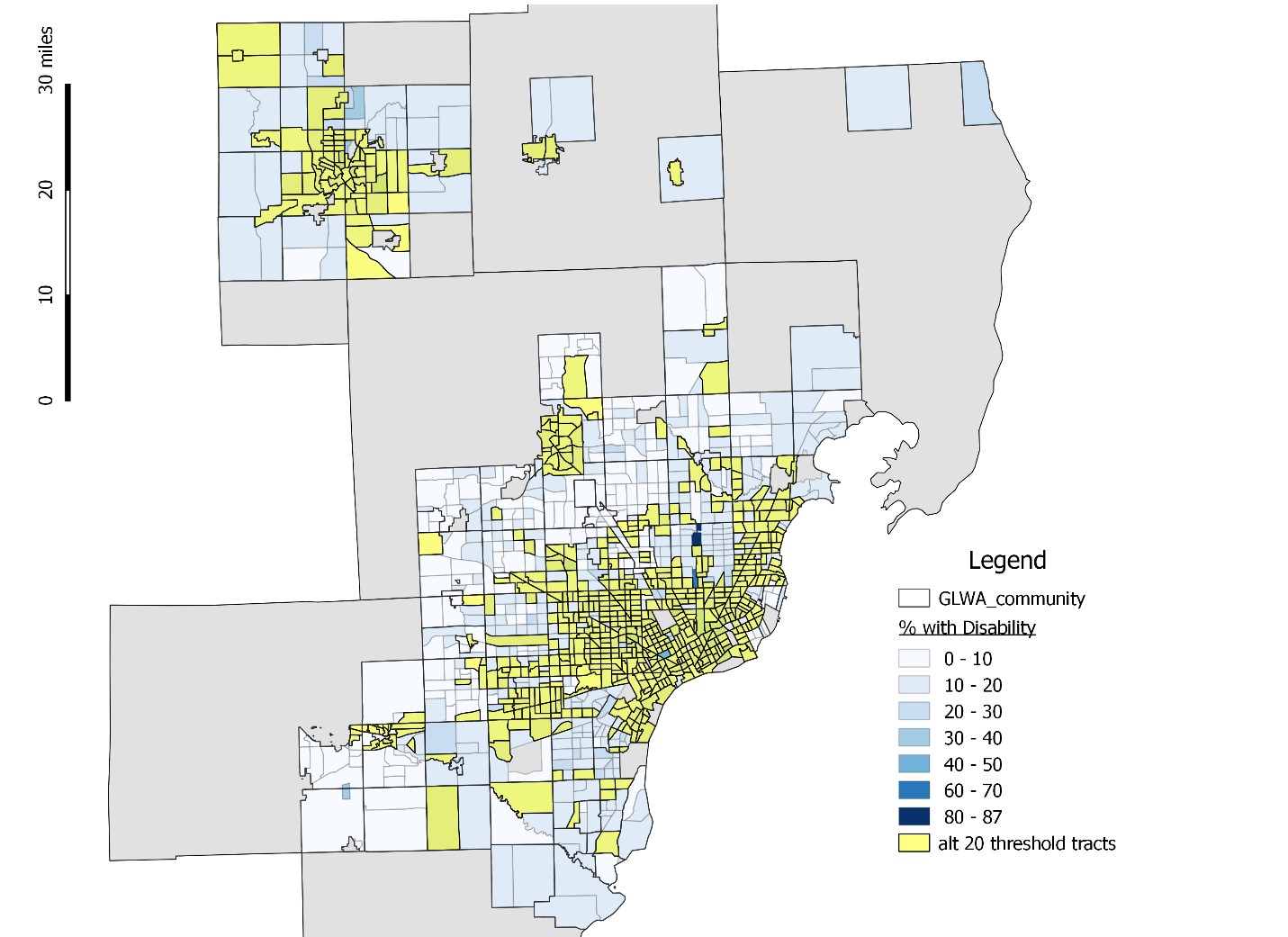

Lastly, similar comparisons can be drawn between the percentage of the population with a disability90 and the tracts that rise above the 4.5 percent threshold, as seen in Figures 24 and 25.

Figure 24: Census Tracts by Percent with a Disability

Image source: US Census, author calculations

Figure 25: Census Tracts by Percent with Disability and Above 4.5 percent RI Threshold

Image source: US Census, author calculations

Here, the connection between the two is less obvious, since there are more widespread lower percentages of disability across the region that is not limited to the tracts that breach the affordability threshold, but it is still clear that the areas suffering the most intense affordability issues are generally the places that have disability rates above 30 percent.

It is clear that water unaffordability disproportionately impacts already-vulnerable communities.

Trends Over Time

One of the common critiques of existing metrics is that they are static snapshots in time that do not take into account temporal trends. It is important to analyze how demographic and economic patterns shift over time to see what trends the near future may hold, especially when comparing different localities.

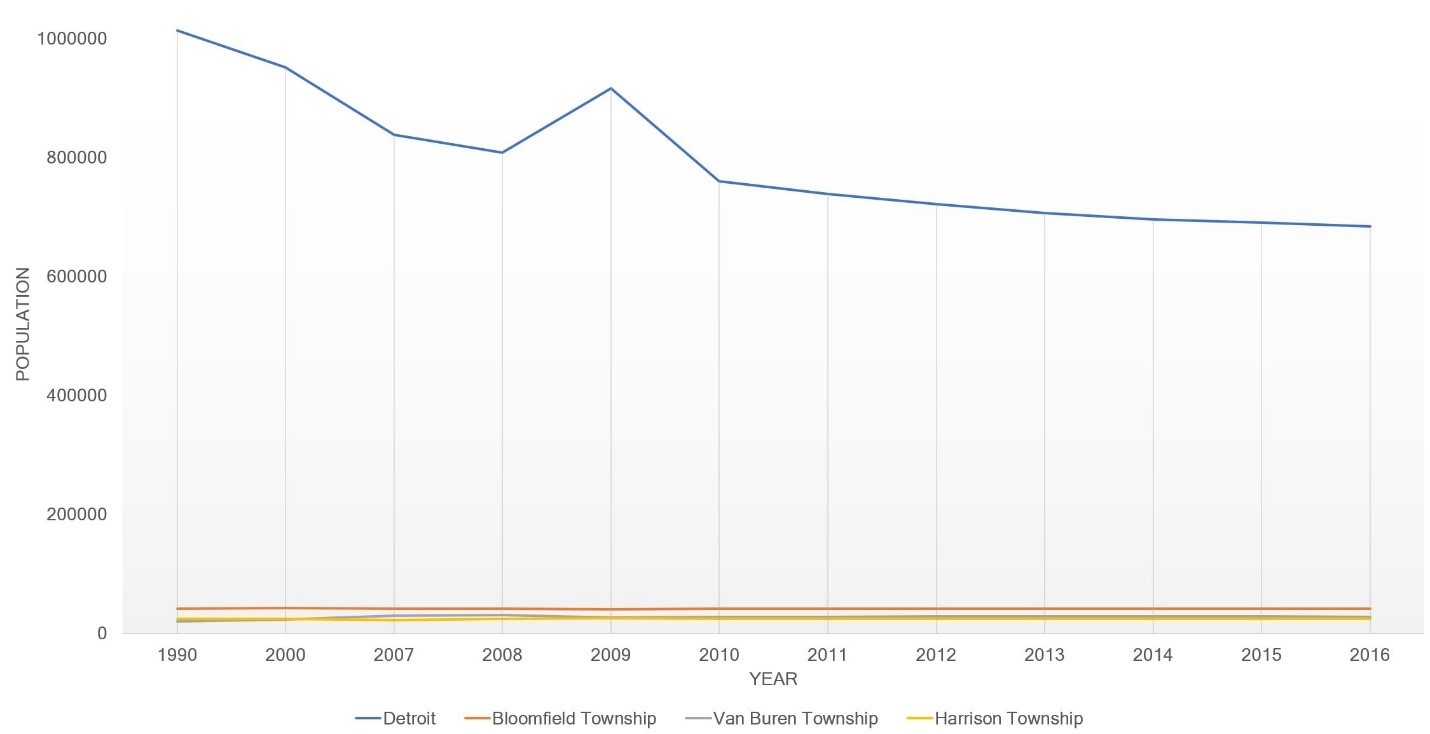

Figure 26, below, shows the population shifts in Detroit (a low-income urban center), Bloomfield Township (a high-income Pontiac suburb), Van Buren Township (a median-income Detroit suburb), and Harrison Township (a median-income township not located near an urban center). These locations represent a sample of different income levels and geographic identities, but still show clear trends.

Figure 26: Population Estimates 1990-2016

Image source: US Census American Community Survey 5-year estimates for 2012-2016, 3-year estimates for 2009-2011, 1-year estimates for 2007-2008, and decennial census for 1990-2000.

Detroit shows a steady and significant decline in population of over 300,000 people, while the individual suburbs grow slightly (Van Buren Township) or stay relatively stable (Bloomfield Township, Harrison Township).91

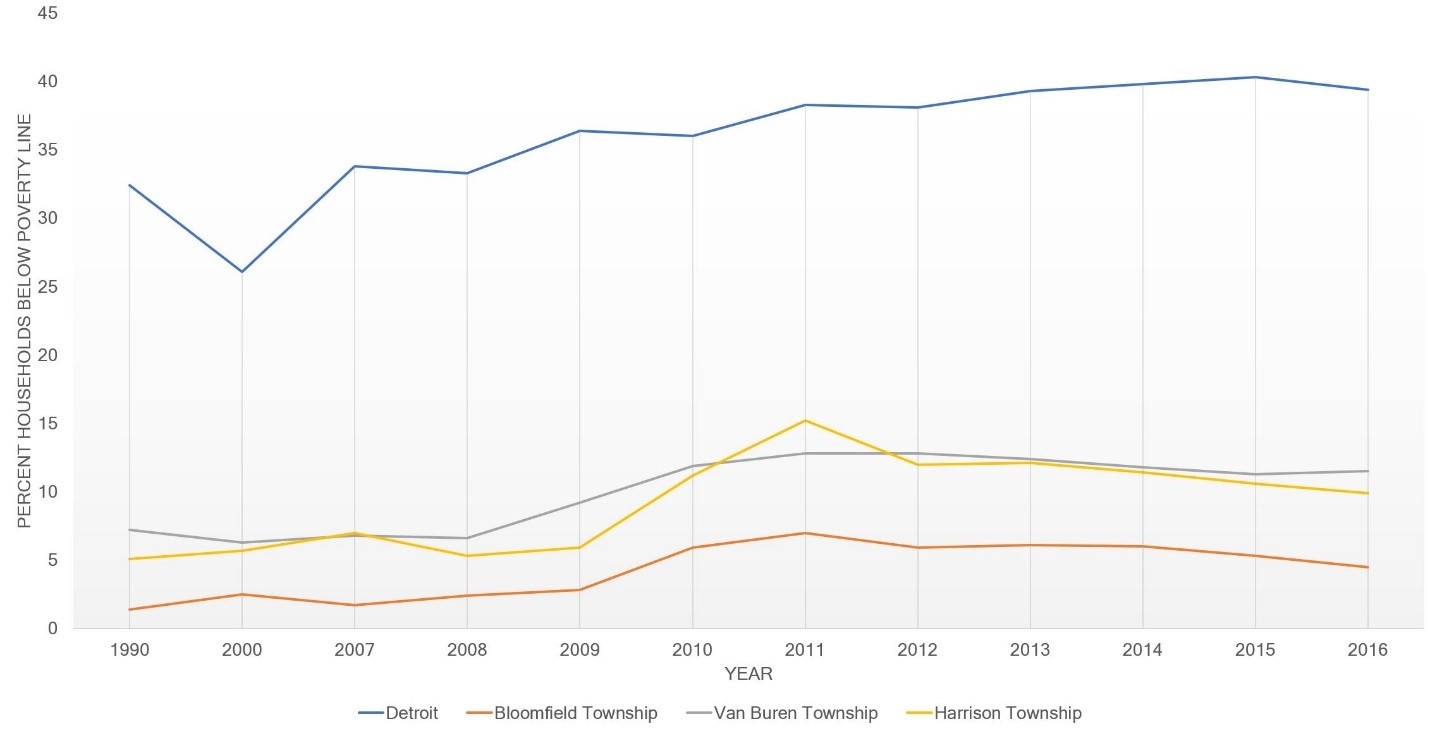

Figure 27 displays poverty rates among the locations over time.92 Although poverty rates climb for all locations in the aftermath of the Great Recession, only Detroit’s was climbing significantly beforehand, and again only Detroit’s shows minimal recovery after the nation’s economic turnaround.

Figure 27: Poverty Rate Estimates 1990-2016

Image source: US Census American Community Survey 5-year estimates for 2012-2016, three-year estimates for 2009-2011, 1-year estimates for 2007-2008, and decennial census for 1990-2000.

It is clear from both trends that the economic and social pressures on utilities in struggling urban centers like Detroit (and by extension Flint and Pontiac) are not on a path to rectify themselves. Increasing poverty rates mean more households will face unaffordability concerns, while shrinking ratepayer numbers due to population decline will also put further strain on utilities that need to spread high fixed costs among a broad customer base.

Alternatives for Addressing Affordability

This section will present and evaluate possible policy options for alternative rate structures and customer assistance programs to address unaffordability issues from both equity (fairness, social impact) and efficiency (utility viability) perspectives. This type of policy discussion is necessarily defined by the unique circumstances of the utility service areas. The following discussion relates to the GLWA and DWSD, but can be read to follow the general principles of what alternative practices could apply elsewhere. Before analyzing alternatives for addressing unaffordability, it is necessary to understand the legal landscape that has characterized decision making and rate setting in Michigan.

Legal Context

State Law

When the question of water affordability plans and their funding is raised, the Headlee Amendment is brought up as a legal barrier to some proposals to create a robust affordability program. A full accounting of the state of cases on this topic is outside the scope of this analysis, but given the number of active cases and the variability in the outcomes so far, as well as conflicting legal memos to come out of official reviews such as the Detroit Blue Ribbon Panel on Affordability, it is clear that the Headlee Amendment and its application in Bolt do not outright prohibit alternatives to cost-based rate setting, and that each is subject to individual interpretation.93 The fact that the Detroit Blue Ribbon Panel on Affordability did not decide to find alternative rate structures unlawful, only subject to “risk of potential legal challenge,”94 illustrates this fact. Interviews with local experts and review of internal decision-making documents indicate that current lack of alternative rate structures is due to desire to avoid said potential legal challenge, rather than a past finding of unlawfulness.

Mich. Const. art. IX, § 31, commonly referred to as the Headlee Amendment, prohibits local governments from raising taxes without voter approval.95 In Bolt v. City of Lansing, the Michigan Supreme Court interpreted a storm water charge that exceeded the actual cost of service as a tax, invalidating it under the Headlee Amendment.96 The court devised a three-part test to differentiate between a tax and a fee, holding that:97

- A user fee is meant for regulation, while a tax generates revenues.

- A user fee must be proportionate to the necessary cost of service.

- Unlike taxes, fees should be voluntary, allowing users the right to refuse the use of a commodity.

The Detroit Blue Ribbon Panel on Affordability stated that the Bolt decision has generally been interpreted to require that water services be priced on the cost of service, rather than alternative rate structures potentially based on non-cost factors like income or ability to pay. However, there is considerable disagreement over the extent to which Michigan’s legal framework applies to alternative rate structures (as opposed to individual charges like the Bolt storm water charge).98

In July 2018, Oakland County Circuit Court Judge O’Brien ruled on a class action case brought on behalf of Bloomfield Township residents. The suit raised multiple issues, one of which asserted that some water and sewer service charges violated the Headlee Amendment. On this point, the judge ruled that there was no violation of Headlee.99

A series of other lawsuits in circuit court have had mixed results, with suits against Birmingham and Ferndale settling out of court and cases against Royal Oak and Holly dismissed in court in 2015 and 2016.100 A single law firm handled many of those cases and has several ongoing cases in Oak Park, Westland, Detroit, Dearborn, and Brighton Township.101 Oak Park has taken its case to the Michigan Court of Appeals.102

Federal Law

Beyond state law, federal laws and regulations expressly allow variable rate structures. EPA regulations state very clearly that grantees (local jurisdictions regulated by EPA) “may establish lower user charge rates for low income residential users after providing for public notice and hearing.”103 Further, EPA states that “[t]he costs of any user charge reductions afforded a low-income residential class must be proportionately absorbed by all other user classes. The total revenue for operation and maintenance (including equipment replacement) of the facilities must not be reduced as a result of establishing a low income residential user class.”104 In addition to regulatory permission, the EPA encouraged regional administrators and directors to consider alternative rate structures, saying that “[u]niform rate structures may place disproportionately high financial burden on households with low incomes. EPA Strongly encourages municipalities to consider establishing lower rates or subsidies for low income customers.”105 Therefore, the EPA not only allows, but expressly encourages, low-income alternative rate structures to be implemented, and to be paid for by spreading costs throughout the rest of the system’s ratepayers.

The Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution declares that federal law supersedes state law when the two conflict.106 The United States Supreme Court has also clearly found in City of New York v. FCC that federal regulations, such as EPA’s, carry the force of federal law:

The phrase “Laws of the United States” encompasses both federal statutes themselves and federal regulations that are properly adopted in accordance with statutory authorization… we have also recognized that “a federal agency acting within the scope of its congressionally delegated authority may preempt state regulation” and hence render unenforceable state or local laws that are otherwise inconsistent with federal law.107

It has been asserted that because GLWA operates under an EPA NDLP permit and receives funding from EPA through State Revolving Funds, EPA regulations apply to the current context as interpreted by the Supreme Court in City of New York v. FCC. It is unclear if this avenue of argumentation has been raised any of the various state cases brought under Headlee/Bolt.

The active nature of state cases and potential avenues for higher level appeals, especially in the context of federal law, mean that the legal context of this topic is uncertain, and fear of legal challenge alone should not prevent further consideration of alternative rate policies, assuming that the long-term potential cost savings of rate reform are larger than legal fees.108

The federal government can also play a role in the design and implementation of affordability programs. For example, on June 6, 2018, Senator Kamala Harris introduced Senate Bill 3015, known as the Water Affordability Act. It would amend the Federal Water Pollution Control Act “to establish a low-income sewer and drinking water assistance pilot program...109 to provide grants to not less than 10 eligible entities to assist low-income households and environmentally at-risk households in maintaining access to sanitation services and drinking water.”110 The bill spells out qualifications for eligible entities and households. Eligible entities must be a municipality or public utility currently “affected by a consent decree.”111 Individuals eligible to receive assistance funded by federal government must be low-income (households at a particular income or enrolled in a number of existing assistance programs), or environmentally at-risk households in areas within 5 miles of an environmentally hazardous site or other area designated as at-risk by the EPA’s Environmental Justice Screen Tool, which uses both racial demographics and environmental risks.112

Policy Alternatives

One way that utilities address affordability issues like those identified above is through Customer Assistance Programs (CAPs). The EPA has published a review of CAPs across the country and found that programs typically span five categories:113

- Bill Discount – reduces the bill, typically long-term

- Flexible terms – arrearage management, bill timing adjustment, payment plans, levelized billing (breaking annual or quarterly payments down to monthly)

- Lifeline rate – subsidized rate for a fixed amount of water for basic needs

- Temporary assistance – short-term or one-time assistance to prevent disconnection or assist with hardship

- Water efficiency – provide assistance for repairs and/or efficiency upgrades

Out of 795 utilities reviewed by the EPA, 228 offered some form of CAP.114 The EPA found that 42 percent of all CAPs were related to bill discounts, while 27 percent were included in flexible terms, and 24 percent applied for temporary assistance. Programs are often targeted based on income, permanent disability, temporary hardship, age, or veteran status.

In late-2015, the Detroit City Council convened a Blue Ribbon Panel on Affordability (BRPA) to study the issue. The panel was comprised of national and regional experts on public utilities, water, and affordability who came from academia, regional utilities, and practitioners. The panel published a report in 2016 detailing its findings.115 Because the panel spent considerable time investigating and ranking policy alternatives, this analysis will not repeat those efforts in full.

However, the panel’s report exposed serious disagreements among members,116 shortages of data and analysis,117 and was published before GLWA’s program meant to address affordability was launched.118 So far, this analysis has endeavored to provide additional data and empirical analysis to inform areas where BRPA and others have admitted open questions remain. The review of alternatives below will report on BRPA’s findings, adding new empirical evidence from the findings in preceding sections and evaluating GLWA’s assistance program that the panel was unable to review.

Customer Assistance Programs

The Water Residential Assistance Program by GLWA and DWSD

GLWA implements a CAP called the Water Residential Assistance Program (WRAP). Eligibility requirements for the program are:119

- Have income at or below 150 percent of the poverty threshold ($30,240 for a family of three)

- Install a new automatic meter-reading device

- Provide proof of residency and income

- Provide renter’s proof of responsibility for water on lease

- Have provided payment towards the account balance (either of 5 percent of amount owed or $50) within last 90 days

- Stay current on monthly bill payment

- Two-year limit to program participation

The benefits of the program to households are:120

- One-time home water audit for households above 120 percent of average water use

- Up to $1,000 for minor plumbing repairs

- Up to $300 per year in monthly bill credits ($25 per bill)

- Up to $700 per year in arrearage assistance