Transgender people face both subtle and overt forms of bias and discrimination in a number of areas including healthcare, housing, education, and employment. They report high rates of homelessness that are linked to high estimates of discrimination in attaining housing. Among these issues, bathroom access has received outside attention, particularly because opposition to transgender equality has been successful in using hateful and inaccurate tropes about transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. For civil rights advocates, however, fighting for equal access to restrooms according to one’s gender identity is a major issue precisely because it underlies discrimination in a variety of different public and private contexts. Bathroom access, in the words of one legal scholar, “manifests as a subset of a larger issue: the ability to secure and hold employment or use places of public accommodation without experiencing discrimination or abuse.” Over a dozen states have considered (and in North Carolina, with HB 2, implemented) bills that would force individuals to use bathroom facilities that are limited to their biological sex at birth. These laws are frequently justified under the guise of protection for women from sexual assault, though researchers have found that there is no evidence that safety and privacy is negatively impacted when restroom use is based on gender identity. While many civil rights groups have launched challenges to regressive bills, researchers argue more proactive visions of bathroom equality are needed to overcome the varied and drastic forms of discrimination faced by transgender populations.

As Haas Institute LGBTQ Citizenship faculty member Sonia Katyal argues, the law has failed to keep pace with the inclusion of burgeoning and diverse transgender and gender non-conforming populations. This policy brief reviews literature on the challenges transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals face in overcoming discrimination and harassment, with particular focus on the role of conditioning restroom access as a key site of social exclusion. Legal challenges to the regressive restroom policy argue that some solutions—such as mandating transgender individuals use a separate single-user facility—do little to address the indignities of unequal access. The brief outlines solutions to address the problem, focusing especially on data collection of gender identity and access needs, as well as strategies in the designing and planning of gender inclusive, rather than gender neutral, bathroom facilities. These strategies will allow policymakers to enable restroom inclusion while addressing concerns about safety, especially focusing on the need to recognize the intersectional needs and concerns bathrooms hold in society.

Key Findings

+As more people start to identify as transgender and gender non-conforming, access to public facilities, free from harassment and discrimination, has become a pressing issue.

+When trying to access public facilities that correspond with their gender identity, transgender and gender non-conforming individuals regularly report exclusionary practices, intimidation, harassment, and in some cases overt violence.

+Evidence suggests that daily anxieties over bathroom use remains a primary concern for transgender and non-conforming populations leading to increased rates of health issues such as urinary tract infections, as well as mental health concerns tied to sustained discrimination and harassment.

+ Bathroom access has played a key role in discrimination faced by many other minority groups, with sex segregation posing a particular challenge to enabling restroom inclusion for diverse gender identities.

+Research by scholars from the Haas Institute LGBTQ Citizenship research cluster highlights the ways gender inclusive bathrooms also benefit other populations including disabled and elderly people who may have attendants of another gender and parents caring for children.

Solutions

+Research by the Haas Institute LGBTQ Citizenship faculty stresses the need for policymakers to develop clear protocols, concrete policies, and workable timelines to ensure that all constituents have access to public bathroom facilities free of harassment or intimidation.

+A more pluralistic and intersectional approach to bathroom access understands that gender inclusive facilities also benefits parents, disabled populations, the elderly, and anyone else who might require assistance from a caretaker.

+A pluralistic approach recognizes the value of women-only facilities, and both single-user and multi-user gender neutral facilities. It also affirms the right of individuals to use the restroom that best corresponds to their gender-identity

+Scholars recognize the importance of genderinclusivity in intake forms and data collection protocols and advocates increased education and training regarding best data collection practices regarding gender and sexuality.

Bathroom & Inclusion

TRANSGENDER PEOPLE face both subtle and overt forms of bias and discrimination in a number of areas including healthcare, housing, education, and employment. They report high rates of homelessness that are linked to high estimates of discrimination in attaining housing. Among these issues, bathroom access has received outside attention, particularly because opposition to transgender equality has been successful in using hateful and inaccurate tropes about transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. For civil rights advocates, however, fighting for equal access to restrooms according to one’s gender identity is a major issue precisely because it underlies discrimination in a variety of different public and private contexts. Bathroom access, in the words of one legal scholar, “manifests as a subset of a larger issue: the ability to secure and hold employment or use places of public accommodation without experiencing discrimination or abuse.”1

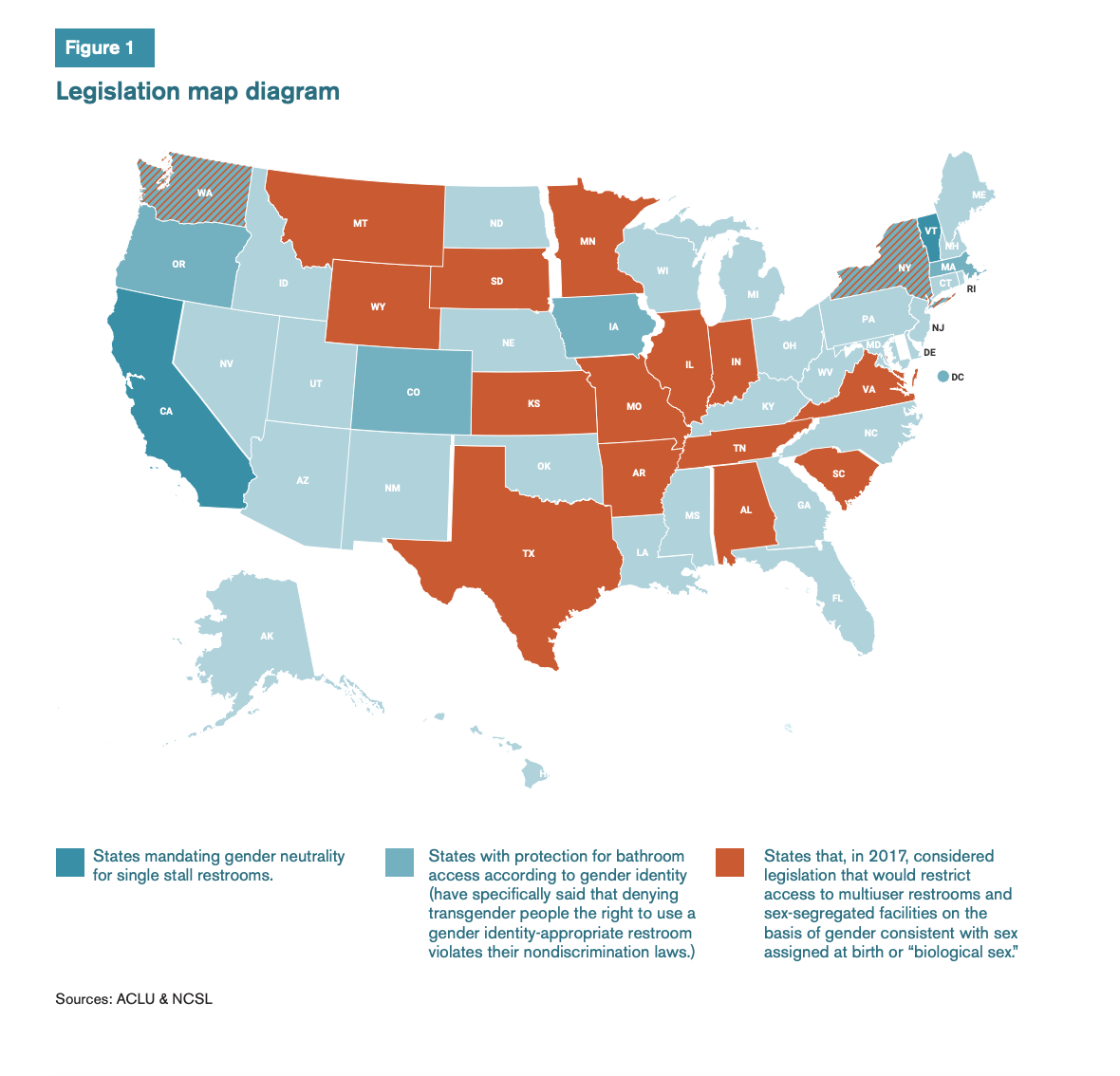

Over a dozen states have considered (and in North Carolina, with HB 2, implemented) bills that would force individuals to use bathroom facilities that are limited to their biological sex at birth. These laws are frequently justified under the guise of protection for women from sexual assault, though researchers have found that there is no evidence that safety and privacy is negatively impacted when restroom use is based on gender identity. While many civil rights groups have launched challenges to regressive bills, researchers argue more proactive visions of bathroom equality are needed to overcome the varied and drastic forms of discrimination faced by transgender populations. As Haas Institute LGBTQ Citizenship faculty member Sonia Katyal argues, the law has failed to keep pace with the inclusion of burgeoning and diverse transgender and gender non-conforming populations.2

This policy brief reviews literature on the challenges transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals face in overcoming discrimination and harassment, with particular focus on the role of conditioning restroom access as a key site of social exclusion. Legal challenges to the regressive restroom policy argue that some solutions—such as mandating transgender individuals use a separate single-user facility—do little to address the indignities of unequal access. The brief outlines solutions to address the problem, focusing especially on data collection of gender identity and access needs, as well as strategies in the designing and planning of gender inclusive, rather than gender neutral, bathroom facilities. These strategies will allow policymakers to enable restroom inclusion while addressing concerns about safety, especially focusing on the need to recognize the intersectional needs and concerns bathrooms hold in society.

Unequal Access

DISCRIMINATORY BATHROOM BILLS ignore the extreme challenges many transgender and gender non-conforming individuals face in gaining access to public facilities. Evidence suggests that daily anxieties over bathroom use remains a primary concern for transgender and gender non-conforming populations and leads to increased rates of health problems such as urinary tract infections, as well as mental health concerns tied to sustained discrimination and harassment. Greater attention to actual trans experiences highlights the need for greater education and widespread understanding of the indiginities and varying challenges gender non-conforming individuals face in accessing public facilities.

Trans persons face a variety of forms of discrimination in the lack of adequate bathroom facilities, including both physical and verbal harassment. In response, many avoid using the restroom sometimes for prolonged periods of time. As result of "holding it” or avoiding relieving oneself, many suffer from weakened bladders and kidneys. Additionally, dehydration is shown to lead to many other long term medical issues. These conditions are just some of the health challenges, which extend to mental health issues, that point to highly unequal health outcomes faced by gender non-conforming populations.

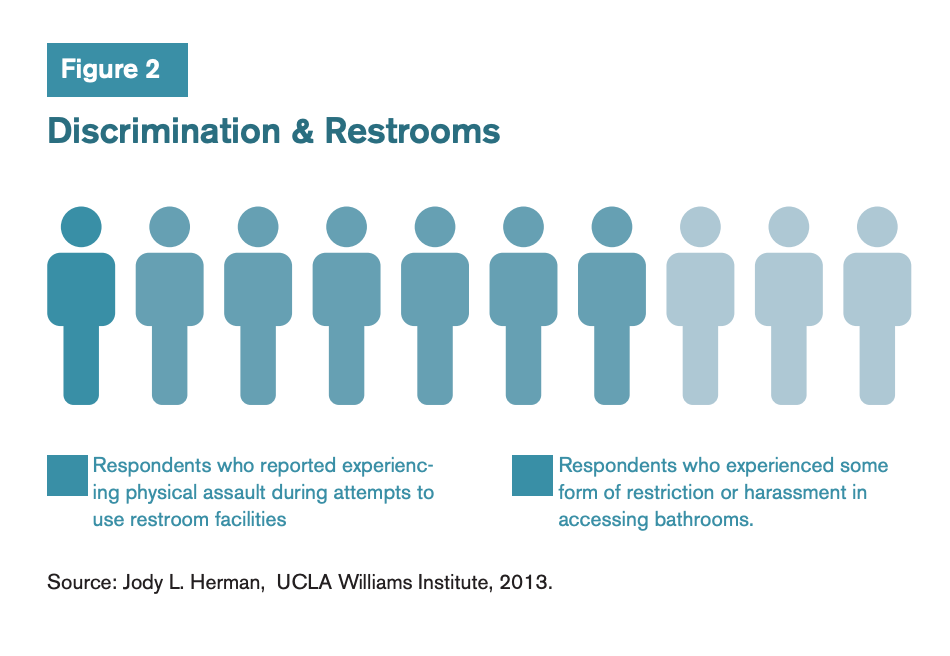

For many transgender individuals, bathroom avoidance allows reprieve from persistent harassment in and around lavatories. In one study of several dozen transgender persons in Washington DC, 70 percent of respondents experienced some form of restriction or harassment in accessing bathrooms. The highest occurrence was verbal harassment. Many respondents recounted their strategies for avoiding harassment, such as attempting to “pass,” in the case of a transwoman, as highly feminine. “It works under 50 percent of the time,” she reported, “I am often still read as a man.”3 Additionally, 9 percent of respondents reported experiencing physical assault during attempts to use restroom facilities. Studies show that race, ethnicity and (to a lesser extent) class can all contribute to the likelihood that transgender persons face discrimination and harassment.

A 2015 legal challenge succeeded in demonstrating that insufficient restroom access constituted a violation of equal access, recognizing the indignity such a lack of access provides. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, citing previous federal court precedents, ruled that barring the employee from using the bathroom consistent with her gender identity was a violation of Title VII employment law. The case, Lusardi v. McHugh, was filed by a civilian employee against the U.S. Army after she was barred from using the women’s room until she received gender reassignment surgery. The suit detailed the persistent challenges she faced particularly after an attempt at accommodation (through a single single-user restroom) failed, forcing her to use multi-user women’s restrooms but face disciplinary action for doing so. The EEOC’s ruling was powerful in recognizing that bathroom access was central to employment and that the employer could not “condition” the use of facilities contingent upon medical surgery status nor restrict the type of facility an individual used. Invoking the aim of Title VII that one group (in this case, cisgender women) could not aim to bar an individual on the basis of their own interest, the EEOC condemned solutions that “isolated and segregated [the defendant] from other persons of her gender. It perpetuated the sense that she was not worthy of equal treatment and respect.” The case highlights the pitfalls of arguments for single-user stalls as a practical remedy, as it places the onus on the transgender individual to conform to this accommodation even when not practical (such as the case that the single-user stall is closed for cleaning or is in disrepair).4 The finding acknowledges that restroom access is central to the inclusion of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals in society.

The Trump administration’s reversal of Obama-era commitments to transgender equality illustrates the need for proactive solutions to address the intrenchant forms of discrimination trans individuals face in meeting a basic need. Despite recent gains in advocacy in some states, and more broadly in popular culture, stereotyped narratives of the dangers of gender identity based bathrooms still dominate. Amid arguments, for instance, for the North Carolina bathroom bill, HB2, conservative lawmakers, in the words of one legal scholar, “embraced the cultural history of sex segregation” that posed women as inherently vulnerable and in need of protection.5 As in other contexts, defenders of sex segregation, in having survivors of sexual assault testify, sought to conflate the real fact of gendered violence with baseless fears that transgender bathroom access was a means to perpetuate it. Transgender bathroom access, North Carolina plaintiffs argued while providing inaccurate evidence, was overwhelmingly motivated by the desire to prey on women. These recurring, and false narratives of trans women preying on cis women point to the need for development of alternative ones focused on inclusion of transgender and gender non-binary individuals. In fact, of the several states which have passed bills ensuring access to facilities according to gender identity, none reported any incidents of assault. As legal scholar Tobias Wolff notes:

There is a vast gap between the actual operation of gender-identity protections, the implementation of which has been uneventful, and the antagonists’ hysterical claims of physical, sexual, and visual invasion of the body.6

Bathrooms and Social Inclusion

RESTROOM ACCESS has played a central role in many significant civil rights movements. Scholars point to the use of fears of the mixing of different bodies in public as a persistent means to undermine social equality causes, from racial and disability equality, to the contemporary othering of the transgendered body. As with public pools and beaches, resistance to desegregation of bathrooms figured prominently in struggles for equal access to public accommodation for African Americans.8 Fears around diverse bathroom use speak to larger visions of society as it serves as a site for the regulation of social inclusion. Efforts to overcome unequal access facing transgender individuals can simultaneously address intersectional needs in restroom access by moving beyond the presumptions embedded in sex segregated restrooms.

Fear of “othered” bodies is enabled not just by social stigma, but by a history of assumptions—one frequently reified by proponents of bathroom bills— about the need for separate bathroom facilities and discriminatory notions of sex. Regulations for sex segregation in bathrooms emerged in relation to industrial-era labor laws “aimed at protecting the vulnerable, weaker bodies of women workers” as they entered the workforce.9 At their foundation, sorted toilet facilities solidified cultural notions of the need for segregation according to gender, race, as well as physical ability (indeed, the need for sex segregation often collapsed assumptions of gender and physical ability). Drawing on the tactics of the civil rights movement, in 1977 the disability rights movement staged sit-ins of government offices across the country to demand enforcement of accessibility laws. A lack of consistent bathroom access figured as central to their protests. While a powerful critique of ableism in built facilities, disability activists did not challenge sex segregation. In fact, the 1990 American with Disabilities Act had explicit provisions against accomodations to “transvestite” and “transexual” persons seeking disability protection, reinforcing fear of "gender fraud" and "intermingling." Scholars argue that disability critiques of the able-bodied individual and transgender demands for greater inclusion are both necessary to undo the exclusions cemented in the normative binary restroom coupling.10 Separate facilities carry a legacy of efforts to segregate by race, class, and physical ability that are solidified into the built environment and pose an enduring challenge to efforts to enable gender inclusion.

Transgender populations reflect a high level of diversity along the lines of race, class and physical ability, pointing to the need for institutions to understand the varied needs of users through community-supported data collection and research. Many Haas Institute LGBTQ Citizenship scholars remain critical of the use of policy to solidify a stable concept of queer identity that overlooks multiple identities and experiences. Moving beyond unsubstantiated fears of trans bodies, policymakers and courts should focus on creating inclusionary policies that ensure equal public access and dignity while working to allow self-definition of identity and identity-based discrimination remedies. Reliance on stereotypes has material implications for trans rights, as well as for women who in the laws are portrayed as passive victims of sexual assault. A large number of groups face persecution by the law based on stereotypes, creating fears among many different groups of being “misclassified.”

Haas Institute LGBTQ research cluster member Russell K. Robinson and David M. Frost argue that laws such as HB2 function through stereotypes—such as unsubstantiated fears of assault by transwomen—with negative implications for many different groups to define their own identity expression. These laws are one example of how the law hampers social change and the need to move beyond inflexible categorization to allow individuals to define their own needs.11 As in health policies that treat gay and bisexual men as a threat, despite LGBT advocacy by the Obama administration, queer advocates can still rely on “overbroad generalizations to make judgements about people that are likely to perpetuate historical patterns of discrimination.”12 These representations can hold negative implications for those outside of these identity groups: namely trans women of color who are statistically most likely to experience sexual violence. Change agents need to recognize intersectionality and “interrelatedness of homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, hetereosexism and cisgenderism.”13 Institutions should work to understand how overlapping identity experiences can lead to unequal access as well as heighten negative health outcomes.

Solutions: Data for Understanding Needs

A PROACTIVE AND pragmatic vision for addressing bathroom access discrimination should focus on understanding the diverse needs of restroom users and creating a pluralistic approach. While policymakers need to overcome negative narratives and stereotypes that underpin discriminatory efforts, they also need processes to more accurately understand the needs in facilities access. LGBTQ Citizenship research faculty Sonia Katyal critiques “the dearth of empirical and policy research on gender pluralism, including the multiplicity of issues and identities within the transgender community and the impact of our legal system on gender self-determination.”14 Nuanced data collection techniques enable individuals to more accurately represent their identities and begin to address this dearth.

Policymakers must aim to balance self-definition imperatives with the need to remedy discrimination. Queer legal scholars and theorists disagree on the question of data collection from the standpoint that “queer” as a category exists to deconstruct the stable identity categories that presumes, for instance, the gender binary. On the one hand, Russell K. Robinson and David M. Frost argue that the goal “should be to permit people freedom to define their gender and sexual orientation according to their own conscience and not denigrate one’s standing in society because one’s gender identity and/or sexual orientation.”15 LGBTQ politics have, with the success of marriage equality, avoided intersectional interests that render many sexual minority groups—especially gender non-conforming and bisexual groups—largely invisible to public policymaking. The law’s rigid focus on binary gender and sexuality is therefore related to an under-representation of a large portions of sexual minority populations (as well as to the unfixed or changing nature of queer practices and identity) in public discourse and in policymaking.

The Haas Institute maintains that to overcome the extreme discrimination as outlined above, and to recognize the fluid lines of gender identity, policymakers should aim for practical implementation of pluralistic solutions. Data collection can allow policymakers and institutions to better understand and make informed decisions around the diverse needs—related to gender as well as other identity categories—individuals have in accessing and using restroom facilities.16 Inclusion of LGBTQ needs among institutional information-gathering will allow policymakers to more accurately understand the health needs of populations with different needs according to sexual and gender identity. To take the example of a different LGBTQ group, studies indicate that bisexual women, despite outnumbering lesbian women in many counts, remain underrepresented. Research highlights that a lack of understanding of their health needs can, as with transgender populations, lead to negative outcomes. A Canadian-based study found that bisexual women are at a much higher risk than lesbians to face serious health concerns (ranging from poor mental health suicide rates to sexually-transmitted diseases) that go undetected.17 At issue in understanding these dynamics is that many policymakers do not recognize the specific needs and do not allow variance within LGBTQ groups, including those who engage in bisexual activities without identifying as lesbian or gay. To address the unequal health experiences of these groups, agencies and activists should, Juana Maria Rodriguez argues, undertake “community-supported ways of collecting data on gender and sexuality in order to parse out the specific ways that sexual behavior and identity impacts research outcomes beyond the categories of heterosexual and homosexual and male and female.”18

Designing for Inclusion

WHILE POLICYMAKERS must adopt changes to allow the inclusion of transgender and gender non-conforming populations within existing bathroom infrastructure, future design strategies can also address unequal access challenges. Data collection, as outlined above, can allow institutions to understand the holistic bathroom uses individuals may require, and guide a more pluralistic approach to accomodations. The industrial two-gender bathroom design is, in many instances, inadequate in meeting the needs of gender non-conforming populations as well as those whose disabilities, family and privacy needs who require other accommodations. While these needs are very different in scope, they share a common interest in the development of new infrastructural approaches to bathroom provision. Institutions should work towards allowing choice in bathroom by increasing the range of types of facilities as needed. This section outlines pragmatic and well as inclusive ideals for overcoming access challenges.

Attempts to move beyond the standard public restroom binary requires addressing both the substantial investment required to undertake infrastructural changes (and the institutional inertia that attends it), as well as cultural resistance.21 Efforts to enable transgender access to restrooms are consistently responded to with appeals to sexist troupes of the risks to female safety. Even on progressive college campuses, activist efforts have faced opposition from conservative anti-LGBTQ groups, with explicitly transphobic messaging. But they also face opposition, sometimes in the form of indifference from mainstream gay and lesbian groups and more frequently from institutional bureaucracies resistant to modify the standardization of sex segregation.22 Building on the greater visibility of transgender issues, recent activism has been more successful. In 2016, for instance, California passed a bill into law mandating all single-user restrooms be designated gender neutral. In the same year, Massachusetts mandated allowing the use of bathrooms according to gender identity.

Creating holistic bathroom equality will ultimately require moving beyond the standard of two sex-segregated multi-user restrooms that exists in most public facilities. While some researchers argue for all facilities to be non-gendered, we recommend that institutions provide at least one gender neutral single-user facility and one gender neutral multi-user facility per area. Following the Lusardi decision, the onus for access should not be placed on those facing widespread discrimination: transgender individuals should not be limited in their access to single gender neutral facilities, a flawed form of “equal access.” The goal should be to enable a diversity of facilities, including ensuring cis and trans gender women access to a separate facility to address privacy and safety concerns. Coupling gender neutral multi-user facilities with a gender neutral single-user facility in the same area will allow individuals choice while ensuring that gender non-conforming individuals have the same access afforded to cisgender users.

Moreover, this approach represents a more practical standard for future facilities that recognizes the problems with replacing one flawed universalism (binary restrooms) with another (total gender neutrality). Transgender scholar Susan Stryker and architect Joel Sanders recently called for abolishing sex-segregated bathrooms altogether as a means to recognizing human diversity in bathroom needs. They argue for European-style enclosed stalls (with floor-to-ceiling doors) and a communal washroom in a single facility, citing it as a trend among Manhattan restaurant and bars. Their solution is ambitious and follows an argument for “a new way of thinking that shifts the argument from gender neutrality to gender diversity and, ultimately, to human diversity.”23

While their solution has several merits and is an ideal to strive for in many contexts, advocating for its universal adoption poses several challenges. First, attempts by activists to break the sex-segregated mold, especially at institutions, has met opposition on many fronts. Additionally, many cisgender and transgender women alike view women-only facilities as necessary for validating their identity and needs.

Replacing the universal sex-segregation model with a different universal for gender neutrality is in some instances impractical and would leave many cis and transgender individuals unsatisfied. Sonia Katyal argues that this solution reflects the pitfalls that come with essentializing identity experiences: “There are dangers in presuming that all people who identify as transgender seek the same thing, a presumption that is categorically flawed.”24 In the same way that rigidities in the binary pose a challenge to those looking to undo highly gendered legal structures, the built environment and bathrooms in particular demand a rethinking of how to create structures that respond to the different needs of women, both cis and transgender, while structuring remedies accordingly. Russell K. Robinson and David M. Frost note that both groups may signal a preference for women-only restrooms—as in the Lusardi case, this inclusion can be a necessary affirmation of inclusion. Meanwhile they argue that “cis women are likely to experience required multi-user gender-neutral bathrooms as an attack on their sense of self—and one imposed in order to favor a small minority.”25 Robinson and Frost argue that the goal “should be to permit people freedom to define their gender and sexual orientation according to their own conscience and not denigrate one’s standing in society because one’s gender identity and/or sexual orientation.”26 To enable inclusion, and recognize the fluid lines of gender identity, policymakers should aim for practical implementation of pluralistic solutions.

- 1Tobias Barrington Wolff, “Civil Rights Reform and the Body,” Harvard Law & Policy Review 6 (2012): 205.

- 2Sonia Katyal. "The Numerus Clausus of Sex" University of Chicago Law Review Vol. 84 Iss. 1 (2017) p. 389

- 3Jody L. Herman, “Gendered Restrooms and Minority Stress: The Public Regulation of Gender and its Impact on Transgender People’s Lives,” The Williams Institute available at https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/gendered-restrooms-…

- 4Tamara Lusardi v. John M. McHugh, Secretary, Dept of the Army; Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2015.

- 5Terry S. Kogan, “Public Restrooms and the Distorting of Transgender Identity,” North Carolina Law Review, 95:1205 (2017), 1230.

- 6Wolff 209.

- 8Wolff 218-220.

- 9Kogan 1214.

- 10David Serlin argues that restrooms for people with disabilities are often gendered in a way which echoes the idea of the dependent female subject, noting that in at least one instance women’s and disabled restrooms were lumped together. Serlin in Harvey Molotch and Lauren Noren, eds., Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing (New York: New York University Press, 2010) 180

- 11Katyal 2017

- 12Russell K. Robinson and David M. Frost, “The Afterlife of Homophobia,” (forthcoming) 21.

- 13Robinson and Frost 74

- 14Katyal 395

- 15Robinson & Frost 75

- 16Moreover, initial research indicates that allowing trans individuals options to self-identify with their preferred names and gender pronouns can, in itself, enable better mental health outcomes such as a reduction in suicidal thoughts. See Russell, Stephen T. et al. “Suicidal Ideation, and Suicidal Behavior Among Transgender Youth,” Journal of Adolescent Health, (2018) https://www.jahonline.org/article/S1054-139X(18)30085-5/fulltext.

- 17Additionally, “45.4 percent of bisexual women have considered or attempted suicide compared with 9.6 percent of heterosexual women, and 29.5 percent of lesbians.” Steele, Leah S., Lori E. Ross, Cheryl Dobinson, Scott Veldhuizen, and Jill M. Tinmouth. “Women’s Sexual Orientation and Health: Results from a Canadian Population-Based Survey.” Women & Health 49.5 (2009) 353–67.

- 18Juana María Rodríguez, “Queer Politics, Bisexual Erasure: Sexuality at the Nexus of Race, Gender, and Statistics,” Lambda Nordica, no. 1–2 (2016), 176

- 21Harvey Molotch, in his discussion of failed attempts to create gender neutral restrooms at New York University, notes that extra design work costs, code exemptions, and bureaucratic indifference are all challenges to efforts for institutional change. Drawing on sociologist Bruno Latour’s work on infrastructure, Molotch posits that large scale projects require active and concerted buy in from a diverse number of different parties, pointing to the need for positive and proactive narratives to create the cultural imperatives for a project like bathroom equality. Molotch in Molotch and Noren (Eds) 202-207.

- 22Gershenson in Molotch and Noren (Eds) 202-207

- 23Joel Sanders and Susan Stryker, “Stalled: Gender-Neutral Public Bathrooms.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 115:4, (October 2016) 782.

- 24Katyal 423

- 25Robinson & Frost 74-75

- 26Robinson & Frost 75.