By Brad Wong

Content Editor - Equal Voice

Originally published on caseygrants.org.

In Florida, returning citizens – or those with felony convictions – are leading a movement by asking: If we’ve paid our debt to society, why are we denied the right to vote? Amendment 4, which is on the November ballot, is capturing nationwide attention.

ORLANDO, Fla. – When Susanne Manning knocked on her neighbor’s door to talk about restoring voting rights to Floridians with felony convictions, the first comment she heard made her recoil: “Why do you care about those f****** convicts?”

Manning, a White woman who once held an office job, mustered clarity in her voice: “I care because I’m a convict.”

“Why is your yard so nice? Look at your yard,” her neighbor replied, referring to her well-maintained lawn and bushes. He seemed to be implying that tidiness made her exempt from prison.

“Where do you think I learned to do all that?” Manning said, her eyes turning red and watering as she recalled the conversation. The man’s wife appeared and took Manning’s campaign literature for Amendment 4. Their door closed.

The right to vote has long been viewed as one of the highest forms of legitimacy, inclusion and power in U.S. democracy. The idea is that despite a citizen’s wealth or background, all votes – in the general sense – are equal on U.S. soil.

"Everyone deserves to be heard."

-Marquis McKenzie of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition

Today, nearly 1.7 million Floridians – or 1 out of every 10 adults in this state with nearly 21 million people – lack the right to vote because of felony convictions, regardless of degree. Convictions include crimes such as theft as well as violations such as driving with a suspended license, intentionally disturbing a commercial shrimp trap in the water or releasing a group of at least 10 helium balloons into the atmosphere.

Against this tough-on-crime backdrop, convicted felons are leading a movement to pass Amendment 4 to ensure their electoral voices are heard and counted. According to The Sentencing Project, they are doing so in the state that has the highest percentage of adults who cannot vote because of felony convictions.

They also are challenging a long-held belief that felons must be condemned forever – even in communities in which they live and pay taxes.

“We’re moving on the idea that you have the right to vote after you’ve paid your debt to society,” says Desmond Meade, executive director of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition (FRRC), which is leading the effort. “The more people who vote, it’s better for democracy.”

Meade and community organizers are working with residents of all political backgrounds, especially in rural communities that might only have hundreds of people. For Meade, who has felony convictions, there is a core belief: That U.S. citizens can vote for whomever or whatever is on the ballot, but voices need to be heard.

If approved on Nov. 6, Amendment 4 would change the Florida Constitution to allow U.S. citizens with felony convictions the right to cast a ballot. But their sentences, including parole or probation, must be finished.

Under Amendment 4, U.S. citizens convicted of murder or sexual offenses will remain disqualified from casting a ballot unless the governor and executive branch cabinet members restore suffrage. In those cases, restoration would be done on an individual basis, according to Amendment 4 language posted online by the ACLU of Florida.

Florida is 1 of 4 states – Iowa, Kentucky and Virginia are the others – that still permanently bars U.S. citizens with such convictions from voting. Of the nearly 1.7 million U.S. citizens in this state who cannot vote, about 1.4 million of them have served their sentences, according to The Sentencing Project.

More than 21 percent of those nearly 1.7 million U.S. citizens in the state are African-Americans, according to the Washington, D.C.-based research organization. Meade, citing a NAACP analysis, says the amount of African-Americans affected could be as high as a third of those 1.7 million state residents.

“This is an ‘everybody’ issue,” says Neil Volz, FRRC political director.

The widespread nature of felony convictions in Florida touches White Americans, U.S. citizens from Puerto Rico, Cuban Americans, about 10,000 veterans of the U.S. military in the state, rural residents and parents who can’t vote for school board members who are setting policy for their children’s public schools.

“What we bring to this game is proximity to the pain,” Meade says. “We’re personally invested in it. How do we take the pain and transform it into purpose?”

Part of that transformation is a new title that convicted felons have embraced for themselves – returning citizens. And they are talking openly to anyone in the Sunshine State and the country about their lives and the need for a better future.

“We’re not right. We’re not left,” Volz says. “We’re forward.”

***

Amendment 4 is a highly watched issue in Election 2018. Samantha Bee, on her TBS show “Full Frontal,” drew national attention to it by having Meade, who is Black, and Volz, who is White, don blazers, T-shirts and pastel colors in a spoof of the main characters from “Miami Vice,” the crime-fighting television show popular in the 1980s. Bee dubbed her video report, “Miami Rights.”

It has attracted attention from John Oliver’s HBO show “Last Week Tonight,” The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, the PBS NewsHour and Mother Jones.

The nearly 1.7 million citizens who cannot vote in Florida is an eye-catching number: On average, that breaks down to more than 25,000 citizens in each of the state’s 67 counties.

Each year, Volz says, an estimated 170,000 Floridians receive felony convictions. Outreach workers say they meet convicted felons simply by knocking on doors.

There is the question of why this state has the felonies it does and why they are linked to the right to vote. While felonies are typically seen as “grave” or “serious” crimes, misdemeanors are viewed as “less serious” violations.

In the 1860s, after the U.S. Civil War, Florida state lawmakers formally ended slavery and eventually approved suffrage rights for newly freed slaves, as Myrna Pérez of the Brennan Center for Justice in New York City told the PBS NewsHour.

State lawmakers also expanded the list of felonies – adding larceny or the “unlawful taking of personal property” – that could disqualify someone from voting, said Pérez, deputy director of the Center’s Democracy Program. She also works for its Voting Rights and Elections project.

The convicted felony designation, which lawmakers added to the state constitution, remains as a legal way to disenfranchise U.S. citizens in Florida, as The Sentencing Project confirms.

Residents point to these head-scratching examples of state felonies:

- Writing a check over a certain dollar amount and with insufficient money in a bank account.

- Driving a golf cart without permission, such as taking one for a joyride.

- Trespassing on a construction site.

As Bee highlighted on “Full Frontal,” tampering with an odometer and possession of marijuana also constitute state felonies.

Florida currently has a way for convicted felons to regain their voting rights: They have to appear, in person, before a state clemency board. It meets four times a year in the state capital of Tallahassee, located in the Panhandle and about 500 miles from Miami, the state’s most populous city with more than 2.7 million people.

A convict must wait five to seven years after he or she has finished a sentence to apply, and the board has about 10,000 backlogged cases, as the PBS NewsHour reported.

Bee and Oliver showed video footage of the state clemency board and Floridians going before the four-person body, which includes the governor, to ask for the right to vote.

On a grassroots level and based on a September visit by Equal Voice News, Amendment 4 is energizing conversations, especially among residents directly affected and interested in what is possible when people come together to seek a solution to a systemic or institutional barrier.

According to the FRRC, Amendment 4 has attracted bipartisan support from big names such as the ACLU, the Koch brothers, the Christian Coalition and Ben & Jerry’s, the ice cream company in Vermont. Ben & Jerry’s has sent its colorful ice cream truck on a statewide tour of Florida to help raise awareness about voting rights.

This current voting rights effort was born in 2011. That’s when Meade realized the policy implementation of the current state clemency board could dim restoration efforts, which were more successful before that year.

Meade borrowed money to print postcards to raise awareness and call for change.

From there, the word spread, one person and one group at a time. Residents discussed the issue at community centers, parks, businesses, churches, synagogues, shopping malls and in the homes of families.

By January 2018, supporters had collected 1.1 million signatures to put the initiative on the state ballot in November. They only needed 700,000 verified signatures to qualify.

“It’s our approach,” Meade says. “We move politicians out of the way.”

***

The main FRRC office in Florida sits in a one-story business complex in the northwest part of Orlando, home to Disney World and its corporate slogan of “Where Dreams Come True.” Across the street is the 2nd Chances Thrift Store, operated by the Baptist church.

It’s a little after 10 a.m. on a Wednesday in September. A large weekend gathering, in which about 900 returning citizens from around the country gathered in this city, is over.

Manning, the FRRC reentry coordinator, is wearing a gray business suit and standing in a meeting room.

She and others talk proudly about how community organizers contacted nearly 82,000 voters in the city, in a span of hours on a Saturday, to talk about Amendment 4. They knocked on doors, sent text messages and spoke with people by phone.

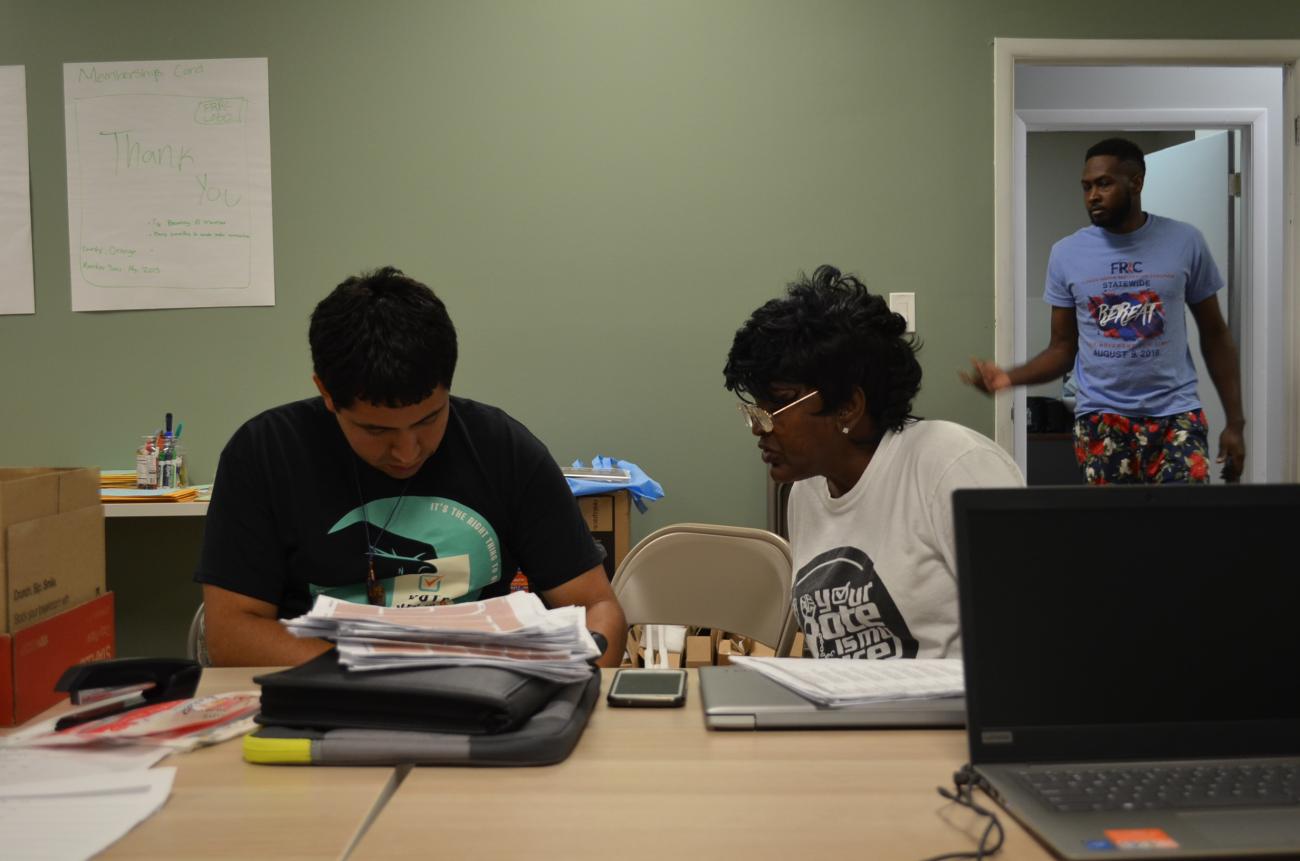

Gale Buswell, a FRRC staff member and returning citizen, is sorting paperwork related to the outreach effort.

“This is about voting. It’s about being whole. This is about our children and our families,” says Buswell, a soft-spoken, Black resident who has regained her voting rights. “This is about being free.”

Nearby, at the end of a table, Maria Morillo, another FRRC staff member, says she supports fellow residents, even though she does not have a felony conviction.

“In Florida, your life can change in minutes,” she says. “There are so many felonies here. It’s easy to get one. We have to touch people’s hearts.”

Later, across the hallway, Manning sits at her desk and reviews a thick stack of resource documents used to support returning citizens with housing, education, banking services, jobs, health care and mental health assistance in each of the state’s 67 counties.

In August, an attorney from the state ACLU invited her to speak about her life and Amendment 4 at a Methodist church in the city.

She accepted, but she felt a wave of apprehension. Would the churchgoers be open to her story? What if she faced hostile questions about convicted felons? Would the risk be worth it?

In front of the churchgoers, Manning shared that she was convicted in the state for grand theft, which sent her to prison in 1993. “I embezzled money from a company,” she says.

While incarcerated, she met other women convicted of theft. She also reflected on her actions. “I made a choice. It wasn’t a mistake. I knew I needed to change,” Manning says.

“Do people change? That was about 30 years ago. I’m a whole different person now. Aren’t we all different people?”

At the end of her talk, people approached to thank her. Several hugged her.

“Sharing your story gives you freedom,” she says, recalling a conversation with Meade. “Stories are power. When I share my story, it gives me strength to go on. I realize my worst secret is on the table.”

***

By about 7 p.m., about 160 miles to the southwest and along the Gulf of Mexico, Volz is standing behind a podium at a community meeting room in Fort Myers. He is conservative and a person of faith.

Volz made the news after his 2006 conviction for bribery as a senior congressional aide in the Jack Abramoff lobbying and corruption scandal in Washington, D.C. Volz cooperated with prosecutors and never spent time in prison.

He left the U.S. capital and eventually settled in Fort Myers, a city with palm trees and posh homes near the water.

Volz is speaking to about 50 people at a local progressive club. “We’re fighting for our friends, our neighbors,” he says, adding that his decisions in Washington, D.C. “blew up” his life and let people down.

He makes the case that all Florida communities will benefit from Amendment 4. He cites a state parole commission study that found that if civil rights are restored quickly to a convicted felon, that person is three times less likely to commit another offense.

“It means safer communities,” he says. “It means less money spent on mass incarceration.”

He also talks about attending an “Americans for Trump” rally earlier in September to discuss Amendment 4. At the rally, a man quietly approached Volz to say he had courage to stand up in public and say he is a convicted felon.

Then, the man acknowledged that he, too, has a felony conviction. He asked for Amendment 4 campaign literature to distribute to people at the rally who are in the same situation.

“All of a sudden, we have common ground,” Volz says.

Volz also has found common ground on Amendment 4 in rural communities in the state, places with about 800 residents.

Opponents do exist. The Center for Equal Opportunity, based in the Washington, D.C. area, argues that convicted felons should not participate in elections, given that they violated the law.

Floridians for a Sensible Voting Rights Policy also questions whether Amendment 4 is prudent for the state.

To win, Amendment 4 needs 60 percent of voters to support it. In late September, a University of North Florida public opinion poll found that 71 percent of state residents are in favor of Amendment 4.

***

Meade, who has earned his law degree but cannot be an attorney in Florida because of his convictions tied to drugs and weapons, says one intent of Amendment 4 was not to put any political party or elected leader at the center of this movement.

Instead, the focus was on families who have experienced the pain and aftermath of felony convictions. He encouraged them to believe in themselves, be part of the conversation, stand up as community leaders and see the positive effects of their actions and of grassroots power.

He envisioned family members sitting around the dinner table, looking at relatives across from them and voting on something directly affecting their lives.

“We need to take back control and view politicians as public servants,” Meade says. “We’ve given power up by apathy.”

On this September evening, FRRC staff members have transformed an office conference room with yellow walls into a photo studio, complete with bright lights and a muted gray backdrop.

Marquis McKenzie, a FRRC staff member in his late 20s, was one of the leaders to come up with the idea for the evening event, “From Mugshots to Headshots,” so returning citizens could have professional photographs to put on their resumes or job applications.

It’s another way, McKenzie says, to help an individual feel like full a person. Returning citizens trickle in to this makeshift photo studio. A few borrow light blue polo shirts with the FRRC logo to wear. The men and women pose and smile for the camera.

At age 14, McKenzie was convicted of robbery and served about two years in a state prison for adult males. There, he read more of the Bible and reflected on the plight of other inmates, some of whom were serving 30-year sentences.

“I realized it was OK to change. I didn’t see myself as a leader until I was in incarceration,” says McKenzie, who is Black and owns a janitorial business.

“Everyone deserves to be heard,” he adds. “Once you get voting, you can change policy.”

In another room, the gathering has blossomed into a brainstorming session. Returning citizens, sitting in folding chairs, suggest ideas and priorities on which to focus to make progress. Volz records the ideas on a white board.

Manning, wearing her gray business suit jacket for her professional headshot photo, is walking in and out of the rooms.

On one day, after that door-knocking encounter in August, she returned home. She noticed someone had trimmed the grass and pruned the bushes, leaving her yard more immaculate than when she left that day.

Manning later spotted her neighbor, the man who used profanity to her face. “I know you’ve been busy. I thought I’d help you out,” he told her.

“Now, he always waves to me when he sees me.”

Brad Wong is content editor for Equal Voice. Equal Voice is Marguerite Casey Foundation’s publication featuring stories of America’s families creating social change. With Equal Voice, we challenge how people think and talk about poverty in America. All original and contracted Equal Voice content – articles, photos and videos – can be reproduced for free, as long as proper credit and a link to our homepage are included.

2018 © Marguerite Casey Foundation